Imagine a place where the best minds of the time gathered to exchange ideas, challenge existing knowledge and push the boundaries of science and philosophy—that was the House of Wisdom.

Jim Al-Khalili.

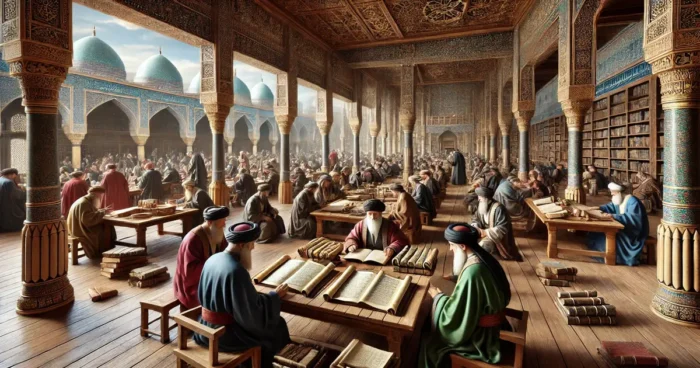

The House of Wisdom (in Arabic Bayt al-Hikmah, بَيْت الْحِكْمَة), established in Baghdad during the Abbasid Caliphate, became one of the most influential centres of knowledge in world history. Founded in the early 9th century, it was a symbol of the Abbasid rulers’ commitment to knowledge and innovation. Scholars from various parts of the world—whether Muslim, Christian, or Jewish—collaborated to translate, preserve, and enhance the classical knowledge inherited from ancient civilizations such as the Greeks, Persians, and Indians.

This article explores the foundation, purpose, key achievements, and lasting significance of the Baghdad House of Wisdom in Islamic and world history.

Origins and Foundation of the House of Wisdom

Historical Background:

The rise of the Abbasid Caliphate in 750 CE marked a transformative era for the Islamic world. After overthrowing the Umayyad Caliphate, the Abbasids sought to establish a new centre of political and intellectual power. In 762 CE, Caliph al-Mansur founded the city of Baghdad on the banks of the Tigris River, strategically located between ancient trade routes. This new capital would soon become a global commerce, culture, and learning centre.

Baghdad’s establishment wasn’t merely a political decision; it was a deliberate move toward making the city a symbol of Abbasid strength, culture, and intellect. Al-Mansur’s vision for Baghdad was one of a cosmopolitan city where scholars, artisans, and traders from various parts of the world could exchange ideas and knowledge. By centralizing power in this new city, the Abbasids fostered an environment where intellectual pursuits could thrive, laying the groundwork for what would eventually become the House of Wisdom.

Foundation of the House of Wisdom:

Note:

The Arabic term “Bayt al-Hikmah” (بيت الحكمة), comprises two words, “Bayt” (بيت): meaning “house” and “Hikmah” (حكمة) meaning “wisdom”, Combined, they form “Bayt al-Hikmah” (بيت الحكمة), literally “Wisdom House” or “House of Wisdom.”

r. = Reigned; denotes the period a ruler or leader held power, specifying the years they ruled.

The seeds for the Baghdad House of Wisdom were planted by Caliph Harun al-Rashid (r. 786–809), one of the most famous Abbasid Caliphs known for his love of learning. Harun al-Rashid was a patron of the arts and sciences. Under his rule, Baghdad flourished as a hub of intellectual activity. Although the House of Wisdom had not yet been officially founded, Harun al-Rashid gathered scholars, established libraries, and encouraged the translation of important texts into Arabic. This intellectual infrastructure set the stage for what was to come.

It was Harun al-Rashid’s son, Caliph al-Ma’mun (r. 813–833), who would formally establish the House of Wisdom (Bayt al-Hikmah) as an institution dedicated to knowledge. Al-Ma’mun’s reign is often seen as the pinnacle of the Islamic Golden Age because of his passionate commitment to scholarship and the advancement of knowledge. Al-Ma’mun expanded the translation efforts initiated by his predecessors, actively seeking out classical works from the Greek, Persian, and Indian traditions to be translated into Arabic. These texts covered a wide range of subjects, including science, mathematics, medicine, philosophy, and astronomy.

Al-Ma’mun also welcomed scholars from various parts of the world to Baghdad, regardless of their religious or cultural backgrounds. Muslim, Christian, Jewish, and Zoroastrian scholars collaborated within the Bayt al-Hikmah, exchanging ideas and knowledge in an unprecedented atmosphere of intellectual openness. This made Baghdad a truly cosmopolitan hub where scholars and scientists of diverse traditions contributed to the growth of knowledge. The result was a unique cultural and intellectual synthesis that would have a lasting impact on both the Islamic world and beyond.

Purpose and Objectives of the House of Wisdom

The Translation Movement:

One of the primary objectives of the House of Wisdom was to spearhead the Translation Movement, a monumental intellectual initiative that aimed to preserve, translate, and expand upon the knowledge of ancient civilizations. This movement began under Caliph Harun al-Rashid and reached its peak during the reign of Caliph al-Ma’mun, transforming Baghdad into the centre of a vast network of scholars who worked tirelessly to translate texts from multiple languages into Arabic.

Scholars at the Bayt al-Hikmah focused on translating key works from Greek, Persian, Sanskrit, and Syriac. These translations encompassed a wide range of subjects, from science, mathematics, and medicine to philosophy, astronomy, and engineering. The goal was not only to translate these works but also to comment on them, expand upon their ideas, and merge them with Islamic intellectual traditions. The Baghdad House of Wisdom became a bridge between the ancient world and the emerging Islamic civilization, ensuring that the knowledge of earlier cultures was not lost but rather enriched.

Key examples of works translated during this period include:

Greek: Plato, Aristotle, Euclid, Galen, etc.

Persian: Zoroastrian and pre-Islamic texts

Sanskrit: Indian mathematics and astronomy

Syriac: Christian and ancient Mesopotamian text

Preservation and Dissemination of Knowledge:

The House of Wisdom not only translated ancient texts but also played a critical role in preserving them. Many of the Greek, Persian, and Indian works that we know today survive because they were translated into Arabic and copied in the libraries of Baghdad. In a sense, the House of Wisdom became a repository of ancient knowledge, safeguarding the intellectual heritage of multiple civilizations.

As the Abbasid Empire grew, so did the reach of the knowledge produced and preserved by the House of Wisdom. The dissemination of this knowledge across the Islamic world, from Andalusia in the West to Central Asia in the East, had far-reaching impacts. Through trade routes, diplomatic missions, and scholarly exchanges, the ideas developed and refined at the House of Wisdom travelled far beyond Baghdad, influencing regions such as Córdoba, Damascus, and Cairo.

This preserved and enhanced knowledge would later be transmitted to Europe through translations of Arabic works into Latin during the European Renaissance. The House of Wisdom thus acted as a conduit for ancient learning, ensuring that the achievements of the classical world would shape the intellectual and scientific progress of Europe in later centuries.

Bayt al-Hikmah as a Public Academy:

The House of Wisdom was not simply a library or translation centre; it functioned as a public academy where scholars could engage in intellectual inquiry, debate, and teaching. It attracted scholars from different backgrounds, Muslim, Christian, Jewish, and others, creating a pluralistic environment where knowledge was pursued for the sake of advancing human understanding.

Unlike modern universities, there were no formal classes or degrees, but the House of Wisdom served as a meeting place for scholars to share their work, collaborate on new ideas, and develop solutions to scientific, mathematical, and philosophical problems. It acted as both a research institute and a place where the ideas of scholars could be tested and refined through discussion and experimentation.

Key Figures and Scholars of the House of Wisdom

The House of Wisdom became renowned for the diversity and brilliance of the scholars it attracted from across the Islamic world and beyond. These scholars, hailing from different regions, cultures, and religions, made groundbreaking contributions in various fields such as mathematics, medicine, philosophy, and astronomy. They were part of a larger intellectual movement that sought to advance knowledge by building upon the works of earlier civilizations.

Let’s explore some of the key figures who were instrumental in making the House of Wisdom a beacon of knowledge.

Al-Khwarizmi (The Father of Algebra):

Perhaps one of the most famous scholars associated with the House of Wisdom is Muhammad ibn Musa al-Khwarizmi (780–850 CE), often called the “father of algebra.” Al-Khwarizmi made foundational contributions to the field of mathematics, especially in developing algebra (from the Arabic word “al-jabr”). His seminal work, “Al-Kitab al-Mukhtasar fi Hisab al-Jabr wal-Muqabala,” (The Compendious Book on Calculation by Completion and Balancing), laid the groundwork for modern algebra and introduced systematic methods for solving linear and quadratic equations.

Al-Khwarizmi’s mathematical texts were not only influential in the Islamic world but also translated into Latin in the 12th century. These translations became standard textbooks in European universities for centuries, profoundly impacting the development of European mathematics during the Middle Ages. His introduction of the Arabic numeral system, which originated from India, and the concept of zero also revolutionized mathematical calculations in Europe, replacing the cumbersome Roman numeral system.

Al-Khwarizmi’s work extended beyond algebra. He made significant contributions to astronomy and geography, producing maps and astronomical tables that were highly regarded. His influence can still be seen today in the word “algorithm,” which is derived from the Latinized form of his name.

Al-Kindi: “The Philosopher of the Arabs”:

Abu Yusuf Yaqub ibn Ishaq al-Kindi (801–873 CE) was one of the most prominent philosophers and polymaths of the Islamic Golden Age. Known as “the Philosopher of the Arabs,” Al-Kindi was deeply involved in philosophy, mathematics, medicine, music theory, and astronomy. He played a key role in introducing Greek philosophy, particularly the works of Aristotle and Plato, to the Islamic world through his translations and commentaries.

Al-Kindi was also a pioneer in the development of cryptography, creating early techniques for breaking ciphers. His works on optics and metaphysics were ahead of their time, merging Greek and Islamic thought. His contributions not only advanced the intellectual pursuits of the Abbasid period but also laid the foundation for later Muslim philosophers such as Al-Farabi and Ibn Sina.

Hunayn ibn Ishaq:

One of the leading translators and scholars at the House of Wisdom was Hunayn ibn Ishaq (809–873 CE), a Christian scholar from Mesopotamia. Known for his expertise in translating Greek medical texts into Arabic, Hunayn was instrumental in preserving the medical knowledge of the Hellenistic world. He translated more than 100 works, including those of Galen and Hippocrates, which were crucial in shaping Islamic medicine.

Hunayn’s translations were so accurate and highly regarded that they became the primary source of medical knowledge for centuries in both the Islamic world and Europe. His contributions greatly expanded the understanding of anatomy, physiology, and pharmacology. In addition to his work on medical texts, Hunayn also translated philosophical and scientific works, playing a critical role in the spread of Greek knowledge.

Ibn Sina (Avicenna):

Ibn Sina (980–1037 CE), known in the West as Avicenna, was a towering figure in both medicine and philosophy. Though he lived after the prime of the House of Wisdom, his works were deeply influenced by the intellectual legacy established during the Islamic Golden Age. His most famous work, “Al-Qanun fi al-Tibb” (The Canon of Medicine), became a standard medical text in both the Islamic world and Europe for centuries, influencing the development of Western medicine well into the Renaissance.

Ibn Sina was not only a physician but also a philosopher who sought to reconcile Aristotelian thought with Islamic theology. His contributions to metaphysics and logic were significant, and his philosophical works had a profound impact on medieval European scholars, particularly in the development of scholasticism.

Other Notable Scholars and Translators:

The House of Wisdom was home to many other intellectual giants, including:

Al-Farabi (872–950 CE): Known as the “Second Teacher” (after Aristotle), Al-Farabi was a renowned philosopher and political scientist who wrote extensively on logic, metaphysics, and ethics. His works bridged the gap between Greek philosophy and Islamic thought.

Al-Razi (Rhazes) (854–925 CE): A Persian polymath, Al-Razi was one of the greatest physicians of the medieval Islamic world. He authored numerous medical texts, including “Al-Hawi,” a comprehensive encyclopedia of medicine.

Thabit ibn Qurra (826–901 CE): A mathematician, astronomer, and translator, Thabit ibn Qurra made significant contributions to geometry and astronomy. He translated many Greek mathematical works and made original contributions to the study of conics.

Al-Battani (858–929 CE): An astronomer and mathematician, Al-Battani made precise astronomical observations and calculated the length of the solar year, influencing later European scientists like Copernicus.

Achievements and Contributions of the House of Wisdom

The House of Wisdom was not merely a centre for collecting knowledge; it was a vibrant institution that facilitated groundbreaking advancements across various disciplines. Its scholars made significant contributions to science, mathematics, medicine, and philosophy, many of which laid the foundations for future developments in these fields. Below are some of the most notable achievements and contributions of the House of Wisdom.

Science and Astronomy:

The House of Wisdom played a pivotal role in the advancement of astronomy, a discipline that flourished under the Abbasid dynasty. Scholars engaged in meticulous observations of the night sky, which led to the development of sophisticated astronomical instruments such as astrolabes, quadrants, and armillary spheres. These instruments enabled astronomers to measure the positions of celestial bodies accurately and predict astronomical events.

One of the remarkable achievements in astronomy during this period was the calculation of the Earth’s circumference. Scholars like Al-Battani (858–929 CE) improved upon earlier measurements and produced remarkably accurate calculations. Their work contributed to a deeper understanding of the universe, challenging previously held beliefs about the geocentric (Earth-centered) model and laying the groundwork for the later heliocentric (Sun-centered) theories developed by Copernicus and others.

Mathematics and Medicine:

The mathematical achievements at the House of Wisdom were groundbreaking and diverse. Al-Khwarizmi’s development of algebra revolutionized mathematics, and his texts laid the groundwork for the subject as we know it today. He introduced methods for solving equations systematically, leading to breakthroughs in geometry and trigonometry.

The concept of zero, also popularized by these scholars, transformed mathematical calculations. The Arabic numeral system, which included zero, replaced the cumbersome Roman numeral system in Europe, facilitating more complex calculations and the advancement of mathematics.

In medicine, the House of Wisdom’s scholars translated and preserved the works of Galen and Hippocrates, among others. These translations formed the backbone of Islamic medicine and were later reintroduced to Europe, where they influenced the Renaissance. The establishment of hospitals and medical schools throughout the Islamic world was partly a result of the advancements made at the House of Wisdom, which emphasized empirical observation and experimentation in medicine.

Ibn Sina (Avicenna), in particular, synthesized the knowledge of Greek physicians and his observations, leading to significant advancements in medical understanding. His work “Al-Qanun fi al-Tibb” became the standard reference for medical students in Europe for centuries.

Philosophy and Humanities:

The preservation and advancement of philosophy were among the House of Wisdom’s most significant contributions. Scholars diligently worked to translate and preserve the works of Greek philosophers like Aristotle and Plato, ensuring that their ideas were not lost to history. This preservation allowed for the continuation of rational thought and inquiry, which became integral to the development of Islamic philosophy.

At the same time, Islamic philosophers such as Al-Kindi, Al-Farabi, and Ibn Sina integrated Greek thought with Persian and Indian philosophical traditions. This unique blend of intellectual traditions fostered the growth of Islamic philosophy, leading to the development of new methodologies and ideas. Scholars examined fundamental questions related to existence, ethics, and the nature of knowledge, influencing subsequent philosophical thought in both the Islamic world and Europe.

The work done at the House of Wisdom not only preserved classical knowledge but also expanded it. Scholars engaged in critical analysis, interpretation, and the synthesis of ideas, resulting in new branches of inquiry that would shape intellectual discourse for centuries to come.

The Fall of the House of Wisdom

The House of Wisdom, despite its illustrious contributions to knowledge and culture during the Islamic Golden Age, ultimately faced a tragic end. The factors leading to its decline and the impact of its fall resonate through history, shaping the future of intellectual pursuits in the Islamic world and beyond.

The Mongol Invasion of Baghdad (1258):

The most significant event leading to the fall of the House of Wisdom was the Mongol invasion of Baghdad in 1258, led by Hulagu Khan, a grandson of Genghis Khan. The siege marked a catastrophic turning point in Islamic history. Baghdad, once a thriving centre of learning and culture, was brutally attacked by the Mongol army. After weeks of siege, the city fell, leading to widespread devastation.

The destruction of the House of Wisdom was particularly heartbreaking. As one of the foremost centres of knowledge, it housed a vast collection of manuscripts, scientific works, and translations that represented centuries of intellectual achievement. During the invasion, countless manuscripts were lost forever as the Mongols systematically destroyed libraries, schools, and centres of scholarship. It is estimated that the Tigris River ran black with ink from the countless volumes thrown into the water, symbolizing the tragic loss of knowledge and history.

Legacy and Impact Despite the Fall:

Despite the tragic end of the House of Wisdom, its legacy endured. The intellectual traditions fostered during its existence continued to influence scholars in both the Islamic world and Europe. The translations and original works produced by scholars of the House of Wisdom were rediscovered during the European Renaissance, a period marked by a resurgence of interest in classical knowledge and philosophy.

Impact on Global Knowledge Transfer:

One of the most significant legacies of the House of Wisdom is its role as a bridge between ancient and modern sciences. During its peak, scholars translated and preserved the works of ancient civilizations, including Greek, Persian, and Indian texts. This preservation allowed for the seamless transfer of knowledge across cultures and time periods. As a result, the foundational ideas and principles that emerged from the House of Wisdom significantly contributed to the Scientific Revolution in Europe during the 16th and 17th centuries. Many scientific advancements that are celebrated today have roots tracing back to the knowledge disseminated through Arabic translations of classical works.

Conclusion

The Baghdad House of Wisdom, or Bayt al-Hikmah, was more than just a library, it was a centre of learning that shaped the course of human knowledge. Its contributions during the Islamic Golden Age, despite its fall, left an indelible mark on history, influencing both the Islamic world and Europe. The spirit of the House of Wisdom continues to inspire modern institutions and intellectual pursuits today.

Some Frequently Asked Questions

What was the House of Wisdom?

The House of Wisdom, also known as Bayt al-Hikmah in Arabic, was an intellectual center in Baghdad during the Islamic Golden Age. It served as a library, translation institute, and academy where scholars from different backgrounds collaborated to translate, preserve, and enhance knowledge from ancient civilizations, including Greek, Persian, and Indian texts. It was pivotal in advancing science, mathematics, medicine, philosophy, and astronomy.

When was the House of Wisdom founded?

The foundation of the House of Wisdom was formally established during the reign of Caliph al-Ma’mun (813–833 CE). However, its intellectual roots were planted earlier by Caliph Harun al-Rashid (786–809 CE), who encouraged learning and translation efforts in Baghdad.

How did the House of Wisdom fall?

The House of Wisdom fell as a result of the Mongol invasion in 1258, led by Hulagu Khan. The city of Baghdad was devastated, and the institution, along with its vast knowledge resources, was destroyed. The Tigris River is said to have run black with ink from the countless manuscripts thrown into it by the Mongols.

References for Further Reading

- Dimitri Gutas. Avicenna and the Aristotelian Tradition.

- Al Khalili, Jim. The House of Wisdom: How Arabic Science Saved Ancient Knowledge and Gave Us the Renaissance.

- Seyyed Hossein Nasr. Islamic Philosophy from Its Origin to the Present: Philosophy in the Land of Prophecy.

- Nasr, Seyyed Hossein, and Mehdi Aminrazavi. An Anthology of Philosophy in Persia: From the Safavids to the Present Day. Volume 4.

- George Saliba. Islamic Science and the Making of the European Renaissance.

- Soheil M.Afnan. Avicenna: His Life and Works. George Allen & Unwin Ltd., 1958.

- Jonathan Lyons. The House of Wisdom: How the Arabs Transformed Western Civilization.