The Abbasid Caliphate, more than any other dynasty, defined the Golden Age of Islam, a time when the civilization of Islam became the most powerful and influential on earth.

historian Marshall G. S. Hodgson

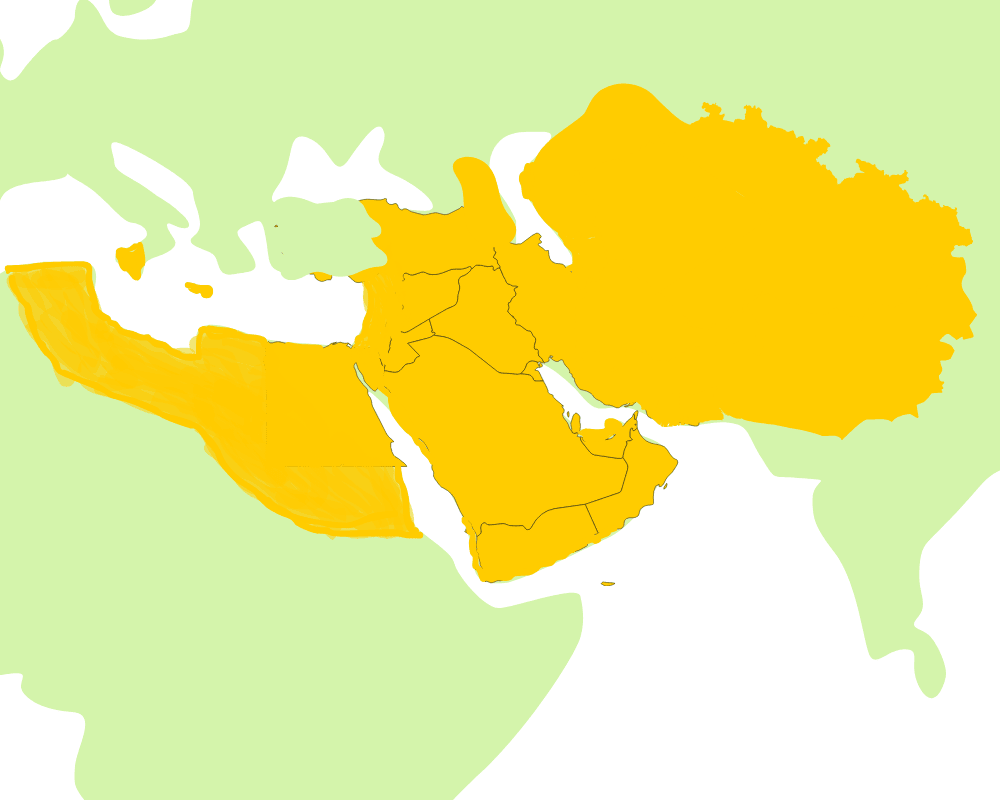

The Abbasid Caliphate (الْخِلَافَة الْعَبَّاسِيَّة or خلافت عباسیہ), which lasted from 750 to 1258 CE, was a period of immense growth and transformation for the Islamic world. Rising after the fall of the Umayyad Caliphate, the Abbasids established their capital in Baghdad, transforming it into a hub of knowledge, trade, and culture. Their reign saw the flourishing of art, science, and architecture, often called the “Golden Age of Islam.” However, like all great empires, the Abbasids eventually experienced decline, weakened by internal strife and external invasions, culminating in their fall to the Mongols in 1258.

This article aims to provide a detailed exploration of the history of Abbasid caliphate, from its rise and remarkable achievements to its eventual fall and the lasting legacy it left behind.

Note:

Empire: An empire is a large, multi-ethnic state or territory governed by a centralized authority, often characterized by military conquest, economic dominance, and cultural exchange.

Caliphate: A caliphate or khilafat is an Islamic state or government led by a caliph, considered the spiritual and temporal successor to the Prophet Muhammad, with authority over the Muslim community (ummah) and responsibility for upholding Islamic law and traditions.

Dynasty: A sequence of rulers from the same family or lineage, often maintaining power over a region or state for several generations, passing leadership through hereditary succession.

Origins and Rise of Abbasid Caliphate

Background and Origins

Abbasid Dynasty Origins: The Abbasid family traced its lineage back to Abbas ibn Abd al-Muttalib, the uncle of the Prophet Muhammad (PBUH). This familial connection to the Prophet gave the Abbasids a legitimate claim to leadership in the eyes of many Muslims. The Abbasids were part of the Banu Hashim clan, a respected branch of the Quraysh tribe. After the Prophet’s death, the family maintained a low profile during the reign of the Umayyads, but they gradually gathered support, especially from those who opposed the Umayyad rule.

Decline of the Umayyads: By the 8th century, the Umayyad Caliphate faced significant challenges. Social unrest, political corruption, and growing inequality spread across the empire. The Umayyads faced opposition from various groups, including non-Arab Muslims (known as mawali, مَوَالِي), Shiites, and many in the eastern provinces who felt marginalized. These groups, combined with economic difficulties and military losses, created a ripe environment for revolution. The Abbasids capitalized on this discontent and promised a more inclusive and just leadership.

Establishment of the Abbasid Caliphate

Revolution: In 750 CE, the Abbasid Revolution, also known as the “Hashimite Revolution,” successfully overthrew the Umayyad Caliphate. The Abbasids, with the help of key figures like the Persian general Abu Muslim, led a revolt against the Umayyads. Abu Muslim was instrumental in rallying support from the eastern provinces, particularly in Khurasan, and uniting various disenfranchised groups, including non-Arabs and Shiites, under the Abbasid cause. The critical battle in this revolution was the Battle of the Zab River, where the Abbasids decisively defeated the Umayyad forces. The last Umayyad caliph, Marwan II, was hunted down and killed, marking the end of the Umayyad reign and the beginning of the Abbasid Dynasty.

Following the overthrow of the Umayyads, the rise of the Abbasid Caliphate transformed the political and cultural landscape of the Islamic world.

The first Abbasid caliph, Abu al-‘Abbas al-Saffah, assumed power after the revolution. His title, al-Saffah, meaning “the Blood-Shedder,” reflected the brutal manner in which he established his rule, ensuring that no Umayyad claimants survived. Despite his harsh beginning, he laid the foundation for the Abbasid dynasty, which would rule for over five centuries. He was instrumental in solidifying Abbasid authority by eliminating rivals and rewarding loyalists.

Establishment of Baghdad as the Capital: Under the rule of Caliph Al-Mansur, the second Abbasid caliph, Baghdad was established as the new capital of the Abbasid Empire in 762 CE, replacing Kufa. Strategically located along the Tigris River, Baghdad quickly became the heart of the empire, surpassing Kufa as a hub for trade, culture, and learning.

Al-Mansur’s vision for Baghdad was grand, and under his leadership, the city began transforming into a flourishing metropolis that would later be known as the “City of Peace” (Madinat al-Salam). Baghdad’s central location allowed it to become a focal point for scholars, merchants, and artisans worldwide, marking the beginning of the city’s golden era.

Key Caliphs of the Early Abbasid Period

Al-Mansur (754–775 CE): Al-Mansur is often credited with consolidating Abbasid power and laying the foundation for future prosperity. He established a strong centralized government and fostered the growth of Baghdad. Under his leadership, the empire experienced significant economic growth due to improved trade routes and administrative reforms. He also focused on building alliances with local rulers, helping to stabilize the empire after its tumultuous beginnings.

Harun al-Rashid (786–809 CE): Harun al-Rashid is perhaps the most famous of all the Abbasid caliphs, known for presiding over the empire during its cultural and intellectual golden age. His reign is often romanticized in literature, such as the tales of The Thousand and One Nights. Under Harun’s rule, Baghdad became a beacon of science, literature, and art. His administration saw advances in science, mathematics, and literature, and his court attracted scholars from across the Muslim world. The empire’s wealth and influence were at their peak during his rule.

Al-Ma’mun (813–833 CE): Al-Ma’mun, another key figure in Abbasid history, was crucial in promoting intellectual achievements and governance reforms. His most notable contribution was the establishment of the Bayt al-Hikmah (House of Wisdom) in Baghdad, which became a leading institution for learning and the translation of Greek, Persian, and Indian works into Arabic. Al-Ma’mun’s reign was also marked by the mihna, a controversial attempt to assert religious authority over scholars, which caused tensions between the Caliph and the religious community.

Early Achievements

Military Conquests: Although the early Abbasid period saw fewer territorial conquests compared to their Umayyad predecessors, the Abbasid military was successful in several key campaigns. One of the early victories was the conquest of Central Asia, particularly the region of Transoxiana. This allowed the Abbasids to maintain control over vital trade routes along the Silk Road. In addition, the Abbasid army fought several battles against the Byzantine Empire, including the defense of Islamic territories in Anatolia and the eastern Mediterranean. While the Abbasids were not primarily known for territorial expansion, their military achievements ensured the stability and defense of the empire, particularly in regions like Khorasan and the eastern frontiers.

Administrative Reforms: One of the early achievements of the Abbasid dynasty was the reformation of its administration. The Abbasids centralized the bureaucracy, making the government more efficient. Persian influence became more pronounced in the Abbasid court, particularly in administration and governance, as many Persian officials were appointed to high-ranking positions. This blending of cultures enriched the empire’s political and cultural landscape.

Economic Growth: The early Abbasid period was marked by significant economic prosperity. The Abbasid Empire controlled vast trade networks that extended from the Mediterranean to the Indian Ocean and beyond. Baghdad became a major hub for trade, linking Europe, Africa, and Asia. Products like textiles, spices, and precious metals flowed through the empire, contributing to its wealth.

Governance and Military Structure

Abbasid Government Structure

Administration: The Abbasid Caliphate’s government was highly centralized and structured, with the Caliph serving as the supreme authority. The administration relied on a sophisticated bureaucratic system influenced heavily by Persian traditions. The Caliph was supported by a series of advisors, viziers (high-ranking officials), and various ministers who oversaw specific aspects of governance. The Abbasids were known for improving the efficiency of government, which allowed them to manage their vast empire effectively despite its diversity in culture, language, and geography.

Provinces and Governance: The Abbasid Empire was divided into multiple provinces, each governed by an appointed leader known as a wali (governor). These provincial governors were responsible for maintaining law and order, collecting taxes, and implementing the Caliph’s policies in their regions. Provinces like Khorasan, Egypt, and North Africa played significant roles in the empire’s administration. While governors had considerable autonomy in managing local affairs, they remained under the close supervision of the caliphate, ensuring that central authority was maintained across the empire.

Bureaucracy: The Abbasids established a professional bureaucracy that was crucial to the functioning of their government. At the center of this system was the office of the vizier, who acted as the chief advisor to the Caliph and was often the most powerful official in the government. Viziers managed the day-to-day affairs of the state, making them key figures in the administration. Below them, various other officials were responsible for the treasury, military, judiciary, and foreign affairs. This structured approach allowed the Abbasids to govern a vast, multi-ethnic empire efficiently.

Abbasid Caliphate Military Organization

Abbasid Caliphate Army: The Abbasid military was a well-organized and formidable force composed of soldiers from different regions of the empire. Recruitment included Arabs, Persians, Turks, and even non-Muslim mercenaries. Over time, Turkish slave soldiers, known as ghilman or mamluks were incorporated into the military, and they became a crucial part of the Abbasid army. The Caliph appointed military leaders, and while the core army was stationed near the capital, regional forces were maintained to protect the empire’s borders. The cavalry was the dominant force, with swift horsemen playing a critical role in both offensive and defensive operations.

Navy: To protect their extensive trade networks and secure their coastal territories, the Abbasids developed a strong naval force. The Abbasid Caliphate Navy was vital for defending the Mediterranean and Persian Gulf coasts and ensuring the safety of sea routes crucial for trade with regions like India, East Africa, and Southeast Asia. The navy was instrumental in fighting off piracy and protecting maritime trade, which was a significant source of wealth for the empire. The rise of the Abbasid navy also allowed for territorial expansion along coastal areas and greater control over the seas.

Abbasid Caliphate Economy and Trade

Economic Policies

Agriculture: Agriculture was the backbone of the Abbasid economy, employing a large portion of the population and providing essential food resources for the empire. The Abbasids invested heavily in improving agricultural productivity by developing irrigation systems, such as qanats (underground canals), and introducing new crops like sugarcane, cotton, and citrus fruits from other parts of the world. These innovations increased yields and supported the growing population of the empire. Regions like Mesopotamia, Egypt, and the fertile lands of the Levant were particularly important agricultural centers, providing grains, fruits, and other produce that fed the Abbasid economy.

Trade and Commerce: Trade was a cornerstone of Abbasid economic strength, with the empire situated at the crossroads of several important trade routes. The Abbasid Caliphate controlled key parts of the Silk Road, which connected the Islamic world with China, India, and Europe. This position allowed the Abbasids to engage in lucrative trade in goods such as silk, spices, precious metals, textiles, and pottery. Abbasid merchants traded as far west as Spain and as far east as Southeast Asia, creating a vibrant, interconnected economy. The caliphate also established strong relations with foreign powers, including the Byzantine Empire, Europe, and African kingdoms, further enhancing its role as a global trade hub.

Currency and Taxation

Abbasid Coins: The Abbasids introduced a standardized currency system based on the gold dinar and the silver dirham, which became widely recognized and trusted throughout the empire and beyond. These coins were minted with inscriptions of Qur’anic verses and the Caliph’s name, signifying both religious and political authority. The stability of the Abbasid currency allowed for the smooth flow of commerce across vast distances, ensuring economic prosperity. The use of uniform currency also facilitated easier trade with other regions, strengthening the empire’s economic ties with foreign markets.

Tax System: The Abbasid tax system was essential to maintaining the empire’s financial stability. Two fundamental forms of taxation were kharaj and zakat.

Kharaj was a land tax levied on non-Muslim landowners, which contributed significantly to the empire’s revenue.

Zakat, a form of charity tax, was obligatory for Muslims and used to support the poor and maintain public welfare.

In addition, taxes on trade and customs duties were collected from merchants traveling along the empire’s trade routes. The effective management of these taxes allowed the Abbasids to fund infrastructure projects, military campaigns, and the luxurious lifestyle of the caliphs.

Baghdad as a Trade Hub: Under Abbasid rule, Baghdad quickly rose to prominence as one of the most important cities in the world. Known as the “City of Peace” (Madinat al-Salam), Baghdad became the heart of global commerce, attracting merchants from Europe, Asia, and Africa. Its bustling markets were filled with goods from distant lands—Chinese silk, Indian spices, African gold, and Persian textiles. As a meeting place of different cultures, Baghdad also became a melting pot of ideas, fostering the exchange of knowledge, art, and science. This cosmopolitan environment helped Baghdad thrive not only economically but also intellectually, as scholars, scientists, and philosophers gathered in the city, contributing to what became known as the Abbasid Golden Age.

The Abbasid Golden Age (8th–13th centuries)

The Abbasid Golden Age refers to a period from the 8th to the 13th centuries during which the Islamic world, under the Abbasid Caliphate, experienced a remarkable flourishing of science, arts, literature, and culture. This era is often described as one of the most intellectually vibrant in history. During this time, scholars from various parts of the world gathered in the empire, contributing to significant advancements that laid the foundation for modern science and philosophy. The achievements of the Abbasid Golden Age are not only pivotal to Islamic civilization but also to the broader history of human knowledge.

When talking about the Abbasid Golden Age, we can’t overlook the Barmakid family. They were the grand viziers, with figures like Yahya Barmaki and Ja’far Barmaki playing major roles. As influential advisers and administrators, they actively supported the intellectual movement by funding translations and backing scholars, shaping the cultural and scientific achievements of the era.

Achievements in Science and Technology

House of Wisdom: One of the most iconic institutions of the Abbasid Golden Age was the Bayt al-Hikmah (House of Wisdom بیت الحکمہ) in Baghdad. Caliph Al-Mansur (754-775 CE) established the Translation Center, known as Bayt al-Tarjamah, which was later transformed into the House of Wisdom by Caliph Harun al-Rashid. This institution was further developed and expanded by his son, Al-Ma’mun, becoming a vibrant center for learning and intellectual exchange.

Scholars, both Muslim and non-Muslim, collaborated to translate ancient texts from Greek, Persian, and Indian sources into Arabic. This effort not only preserved classical knowledge but also led to groundbreaking discoveries in science, medicine, and philosophy, significantly contributing to the spread of knowledge throughout the Abbasid empire and beyond.

Inventions and Innovations: The Abbasid Golden Age witnessed groundbreaking contributions to various fields:

Mathematics: The Abbasid scholar Al-Khwarizmi is known as the “father of algebra.” His works introduced the term “algebra” (from al-jabr) and explained methods of solving linear and quadratic equations. His book, Kitab al-Jabr wal-Muqabala, became a foundational text in the study of mathematics.

Astronomy: Abbasid scientists made significant advances in astronomy. They improved astrolabes (ancient tools for determining time and celestial events) and refined models of planetary motion. Al-Battani accurately calculated the solar year and provided important corrections to Ptolemy’s astronomical work.

Medicine: Physicians like Al-Razi (Rhazes) and Ibn Sina (Avicenna) made enormous strides in medical science. Al-Razi is famous for his works on smallpox and measles, while Ibn Sina’s Canon of Medicine became a standard medical text in both the Islamic world and Europe for centuries.

Engineering: Mechanical inventions were also prominent, with innovators like the Banu Musa brothers contributing to the field of automated devices, including the development of complex machines and tools.

Art and Architecture

Abbasid Architecture: Abbasid architecture reflected both practical and aesthetic advancements, with an emphasis on creating grand and monumental structures. One of the defining architectural feats was the construction of Baghdad itself, designed as a round city with defensive walls and palaces at the center. Abbasid mosques, like the Great Mosque of Samarra, were known for their unique spiral minarets, grand courtyards, and intricate stucco decoration. The use of brickwork and geometric patterns in palaces and religious buildings became a hallmark of Abbasid architecture.

Art and Calligraphy: In the Abbasid period, Islamic art saw a shift toward non-figurative decoration, emphasizing arabesque patterns, geometric designs, and calligraphy. Calligraphy, particularly the Kufic script, became a dominant form of artistic expression, often used to decorate mosques, books, and even household objects. Abbasid artisans also excelled in creating beautiful ceramics, textiles, and metalwork, which were often decorated with intricate designs and inscriptions.

Literature and Philosophy

Abbasid Literature: The Abbasid era was a golden period for Arabic literature. Poetry and storytelling flourished, with works such as One Thousand and One Nights (Alf Layla wa-Layla) capturing the imagination of people across the empire. This collection of tales, including the stories of Aladdin, Ali Baba, and Sinbad the Sailor, is one of the most famous literary achievements of the Islamic world. Abbasid poets, such as Abu Nuwas and Al-Mutanabbi, were also known for their mastery of Arabic verse, often addressing themes of love, politics, and philosophy.

Philosophy: Islamic philosophy thrived under the Abbasids, particularly with the introduction of Greek philosophical texts translated into Arabic. Philosophers such as Al-Kindi, Al-Farabi, and Ibn Sina (Avicenna) engaged deeply with the works of Aristotle and Plato, blending them with Islamic theology. Al-Kindi, known as the “Philosopher of the Arabs,” was the first to systematically reconcile Greek philosophy with Islamic thought. Al-Farabi is credited with contributions to political philosophy and metaphysics, while Ibn Sina’s works on philosophy and medicine profoundly influenced both the Islamic world and later European scholars.

Abbasid Caliphate Social Structure and Society

Social Hierarchy

The Abbasid Caliphate had a highly stratified society with distinct social classes, each playing an essential role in maintaining the empire’s cultural, political, and economic framework. This hierarchy allowed for a structured society where everyone had their place and responsibilities.

Caliphs and Elites: At the top of the social structure were the caliphs, who were not only political leaders but also seen as religious figures and protectors of the Islamic community. The Caliph was the head of state and held ultimate authority over the vast Abbasid Empire. Below the caliphs were the elites, including governors, military leaders, and high-ranking officials. This class also encompassed wealthy landowners and aristocrats, who often played influential roles in local politics and the management of estates.

Scholars and Intellectuals: Under the Abbasids, scholars and intellectuals held a prestigious position in society. The Caliphate heavily promoted the pursuit of knowledge, and intellectuals were respected for their contributions to fields such as theology, philosophy, science, and literature. Many of these scholars were supported by the state, with institutions like the House of Wisdom in Baghdad offering them a place to study, translate, and produce knowledge. The scholar class often influenced political decisions, especially in matters of religious law and governance.

Merchants and Artisans: The merchants formed a critical class in the Abbasid economy. Due to the caliphate’s strategic position along major trade routes like the Silk Road, merchants were vital in facilitating the exchange of goods between the Islamic world, Europe, Africa, and Asia. Cities like Baghdad, Basra, and Cairo became bustling centers of commerce, where merchants traded luxury goods such as silk, spices, textiles, and precious metals.

Artisans were also key players in the Abbasid economy, producing high-quality goods like ceramics, textiles, metalwork, and jewelry that were sought after across the world. These artisans, often working in specialized guilds, contributed to the empire’s cultural wealth through their craftsmanship.

Family and Daily Life

Abbasid Caliphate Family Life: Family life in the Abbasid Caliphate followed traditional Islamic values but was also shaped by the vast diversity of cultures within the empire. Patriarchy was the dominant structure, with the male head of the household holding authority over family matters. Extended families were common, and social obligations often extended beyond the immediate family to include distant relatives and in-laws. Marriage was considered an important social contract, and the role of the family was central in maintaining the social fabric of Abbasid society.

Children were educated in basic Islamic teachings, and wealthier families often employed tutors to teach subjects such as mathematics, literature, and science. Charity and hospitality were highly valued, and family celebrations, such as weddings, were large, community-centered events.

Women in the Abbasid Caliphate: The status of women in the Abbasid Caliphate was varied, with some enjoying relative freedom and influence while others faced significant restrictions. Women from wealthy families had access to education and could participate in intellectual life, though their public presence was often limited due to cultural norms. Notably, some women contributed to the cultural and scholarly landscape, such as Zubaidah bint Ja’far, wife of Caliph Harun al-Rashid, who was known for her patronage of public works, including the construction of water systems for pilgrims.

Regarding legal rights, women in the Abbasid Caliphate could own property, inherit wealth, and engage in business. However, their roles were still largely confined to the household, with social expectations emphasizing child-rearing and domestic duties. In some instances, women wielded significant power within the royal court, particularly as wives or mothers of influential caliphs.

Decline and Fall of Abbasid Caliphate

Despite its remarkable achievements and long-standing dominance, the Abbasid Caliphate eventually succumbed to a series of internal and external challenges. These pressures, both within and beyond the empire, led to its decline and ultimate collapse.

Internal Struggles and Fragmentation

Factions and Rebellions: As the Abbasid Caliphate expanded, it struggled to maintain centralized control. Local dynasties and powerful factions emerged, weakening the authority of the caliphs.

Examples include the Buyids and Samanids, who established semi-independent states while only nominally recognizing the Caliph. In regions such as Egypt and Persia, other local powers rose to prominence, further fracturing the empire. These rebellions and factional disputes created instability, making it difficult for the central government to enforce its rule across vast territories.

Power Struggles: Within the Abbasid court, power struggles exacerbated the internal chaos. Caliphs frequently clashed with their viziers, military commanders, and other officials, resulting in political intrigue and coups. The increasing influence of viziers and military leaders diminished the caliphs’ authority, as these figures often governed in their name while pursuing their own agendas. Such internal conflicts led to civil wars and drained the empire’s resources, accelerating its decline.

External Threats

Challenges from Seljuks and Fatimids: Long before the Mongol invasion, external forces had already weakened the Abbasid Caliphate. The Seljuks, initially employed as mercenaries, gained substantial power and control over much of the caliphate’s territory by the 11th century. The Abbasid caliphs were relegated to symbolic figures, holding only spiritual authority, while the Seljuks dominated the political and military spheres.

Simultaneously, the Fatimid Caliphate, which arose in North Africa and later expanded into Egypt, posed a significant threat. As followers of a different Islamic branch, the Fatimids sought to replace the Abbasids as the legitimate rulers of the Muslim world. This rivalry further destabilized the Abbasid state and hampered its ability to unify its territories.

Mongol Invasion: In 1258, the Abbasid Caliphate faced its greatest external threat—the Mongol invasion led by Hulagu Khan. The Mongols besieged and sacked Baghdad, destroying the city that had once been a center of knowledge and culture. The last Abbasid caliph, Al-Musta’sim Billah, refused to surrender, which led to the fall of Baghdad and his execution at the hands of the Mongols. This marked the end of Abbasid political authority, with the caliphate reduced to a symbolic presence in Cairo under the Mamluks.

Although the Abbasid Caliphate continued in a much-diminished form in Cairo under the protection of the Mamluks, it no longer held any real political authority. The Mongol invasion and the fall of Baghdad marked the end of an era, and the once-great empire was reduced to a mere shadow of its former self.

Abbasid Caliphate Legacy

The Abbasid caliphate’s legacy extends far beyond its political and military power, leaving a profound and lasting impact on Islamic civilization, governance, and global culture. The Abbasids are remembered for their contributions to science, arts, philosophy, and administration, many of which continue to influence the world today.

Cultural and Intellectual Legacy

Lasting Influence: The Abbasid Caliphate is best remembered for the cultural and intellectual advancements that took place during its reign, particularly during the Golden Age of Islam. The caliphs’ patronage of scholars, scientists, and artists led to remarkable achievements in various fields, including mathematics, medicine, astronomy, and philosophy. The House of Wisdom (Bayt al-Hikmah) in Baghdad, a key center for the translation of ancient Greek and Persian texts, played a pivotal role in preserving and advancing knowledge. Scholars like Al-Khwarizmi, the father of algebra, and Ibn al-Haytham, a pioneer in optics, were part of this thriving intellectual atmosphere. The Abbasid period became a model of knowledge creation and cultural flourishing that shaped Islamic civilization for centuries.

Significance in Islamic History

Golden Age Achievements: The Abbasid Golden Age had a lasting impact on various fields of human endeavor, leaving an indelible mark on the course of Islamic and global history. The works produced during this time, particularly in science, philosophy, and the arts, continued to be studied and built upon for centuries. The development of Arabic literature, epitomized by the famous collection of stories One Thousand and One Nights, and the flourishing of Islamic art and architecture, including intricate designs, calligraphy, and mosque construction, showcased the depth and richness of Abbasid culture. The Abbasid era also saw the rise of Islamic philosophy, with thinkers such as Al-Kindi and Al-Farabi contributing to ethical, metaphysical, and political thought, blending Islamic teachings with ancient Greek philosophy.

Rediscovery of Abbasid Contributions: During the European Renaissance, the knowledge produced and preserved by the Abbasids was rediscovered by Western scholars. Many of the scientific, medical, and philosophical texts translated and written during the Abbasid period were introduced to Europe through Spain (Al-Andalus) and Sicily, where Muslims, Christians, and Jews interacted in intellectual and cultural exchanges. The works of scholars such as Avicenna (Ibn Sina) in medicine and Averroes (Ibn Rushd) in philosophy were studied in European universities, playing a vital role in the revival of learning and the development of the Renaissance. Thus, the Abbasid Caliphate’s legacy continued to shape the modern world through its contributions to human knowledge.

Conclusion

The legacy of the Abbasid Caliphate continues to shape Islamic civilization and the broader world today. Its contributions to science, governance, literature, and art helped define an era of unparalleled intellectual and cultural growth. The caliphate’s administrative structures influenced future Islamic empires, while its cultural and intellectual advancements, particularly during the Golden Age, were rediscovered in Europe during the Renaissance.

Frequently Asked Questions

Who Were the Abbasids?

The Abbasids were a Muslim dynasty that ruled the Islamic world from 750 to 1258 CE. They were descended from Abbas ibn Abd al-Muttalib, the uncle of the Prophet Muhammad.

When did the Abbasid Caliphate start?

The Abbasid Caliphate began in 750 CE when they overthrew the Umayyad Caliphate.

How Many Abbasid Caliphs Were There?

There were approximately 37 Abbasid caliphs, with the title being held by various leaders until the fall of the caliphate. The most notable of these caliphs include Al-Mansur, Harun al-Rashid, and Al-Ma’mun.

Why Is the Abbasid Caliphate Regarded as a Golden Age?

The Abbasid Caliphate is considered a golden age due to its significant advancements in science, arts, literature, and culture. The period saw the flourishing of Islamic civilization and the establishment of renowned institutions like the House of Wisdom.

Which Abbasid caliph laid the foundation of Baghdad?

Under the rule of Caliph Al-Mansur, the second Abbasid caliph, Baghdad was established as the new capital of the Abbasid Empire in 762 CE, replacing Kufa.

What Is the Abbasid Caliphate Known For?

The Abbasid Caliphate is known for its contributions to art, literature, science, and philosophy. It was a period of great cultural exchange and innovation, with notable achievements in mathematics, astronomy, and medicine. The caliphate also established a vast trade network and fostered a diverse society.

How long did the Abbasid Caliphate last?

The Abbasid Caliphate lasted for approximately 508 years, from 750 to 1258 CE.

When Did the Abbasid Caliphate Fall?

The Abbasid Caliphate effectively fell in 1258 CE when the Mongol Empire, led by Hulagu Khan, besieged Baghdad, resulting in widespread destruction and the end of Abbasid rule in the city.

What Happened After the Abbasid Caliphate Fall?

After the fall, the Abbasid Caliphate continued in a diminished form in Cairo under the Mamluks, but lost its political authority. The Mongol invasion marked the end of the Abbasid era, and the empire was eventually divided into smaller states.

References

- Kennedy, Hugh. The Early Abbasid Caliphate: A Political History. Cambridge University Press, 1981.

- Lapidus, Ira M. A History of Islamic Societies. 3rd Edition. Cambridge University Press, 2014.

- Al-Jubouri, I. M. N. History of Islamic Philosophy: With View of Greek Philosophy and Early History of Islam. Authors Online, 2004.

- Kennedy, Hugh. The Court of the Caliphs: When Baghdad Ruled the Muslim World. Phoenix, 2004.

- Hourani, Albert. A History of the Arab Peoples. Belknap Press, 1991.

- Kraemer, Joel L. Humanism in the Renaissance of Islam: The Cultural Revival During the Buyid Age. Brill, 1986.

- Zaman, Muhammad Qasim. Religion and Politics Under the Early Abbasids: The Emergence of the Proto-Sunni Elite. Brill, 1997.

- Bosworth, C. E., ed. The History of al-Tabari, Volume 30: The Abbasid Caliphate in Equilibrium. State University of New York Press, 1989.

- Sauvaget, Jean. Introduction to the History of the Muslim East: A Bibliographical Guide. University of California Press, 1965.

- Encyclopaedia Britannica. “Abbasid Caliphate.”

- M.A. Shaban. The Abbasid Caliphate

- Tariq Ali. The Abbasids: The Golden Age of Islam

- Jim Al-Khalili. The House of Wisdom: In Search of Lost Islamic Heritage