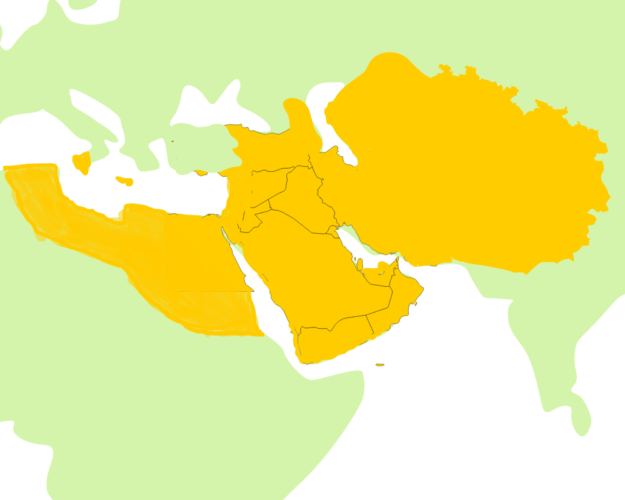

Here is the complete list of Abbasid caliphs whose reigns shaped the destiny of the Islamic world. This list of Abbasid caliphs in order covers the names and reigns of all 37 caliphs, from the dynasty’s inception with Abu al-Abbas as-Saffah, the first Abbasid Caliph in 750 CE to its final days under Al-Mustansir, the last Abbasid Caliph, in 1258 CE.

Chronological List of Abbasid Caliphs

Caliph: The political and religious leader of the Islamic community, regarded as the successor to Prophet Muhammad.

- Abu al-Abbas as-Saffah (750-754 CE) أبو العباس السفاح

- Al-Mansur (754-775 CE) المنصور

- Al-Mahdi (775-785 CE) المهدي

- Al-Hadi (785-786 CE) الهادي

- Harun al-Rashid (786-809 CE) هارون الرشيد

- Al-Amin (809-813 CE) الأمين

- Al-Mamun (813-833 CE) المأمون

- Al-Mutasim (833-842 CE) المعتصم

- Al-Wathiq (842-847 CE) الواثق

- Al-Mutawakkil (847-861 CE) المتوكل

- Al-Muntasir (861-862 CE) المنتصر

- Al-Mustain (862-866 CE) المستعين

- Al-Mutazz (866-869 CE) المعتز

- Al-Muhtadi (869-870 CE) المهتدي

- Al-Mutamid (870-892 CE) المعتمد

- Al-Mutadid (892-902 CE) المعتضد

- Al-Muktafi (902-908 CE) المكتفي

- Al-Muqtadir (908-932 CE) المقتدر

- Al-Qahir (932-934 CE) القاهر

- Al-Radi (934-940 CE) الراضي

- Al-Muttaqi (940-944 CE) المتقي

- Al-Mustakfi (944-946 CE) المستكفي

- Al-Muti (946-974 CE) المطيع

- Al-Tai (974-991 CE) الطائع

- Al-Qadir (991-1031 CE) القادر

- Al-Qaim (1031-1075 CE) القائم

- Al-Muqtadi (1075-1094 CE) المقتدي

- Al-Mustazhir (1094-1118 CE) المستظهر

- Al-Mustarshid (1118-1135 CE) المسترشد

- Al-Rashid (1135-1136 CE) الراشد

- Al-Muqtafi (1136-1160 CE) المقتفي

- Al-Mustanjid (1160-1170 CE) المستنجد

- Al-Mustadi (1170-1180 CE) المستضيء

- Al-Nasir (1180-1225 CE) الناصر

- Al-Zahir (1225-1226 CE) الظاهر

- Al-Mustansir (1226-1242 CE) المستنصر

- Al-Mustasim (1242-1258 CE) المستعصم

Caliphs of Abbasid Dynasty: Key Achievements and Notable Events

This section provides a concise look at the major achievements, challenges, and pivotal events under all the Caliphs of Abbasid Dynasty. The total number of Abbasid caliphs is divided into three categories:

1. Early Abbasid Caliphs (750–861 CE)

The early caliphs of the Abbasid dynasty were instrumental in establishing the foundation and character of the dynasty. These caliphs helped to secure the Abbasid dynasty’s hold over the Islamic empire, and their reigns were marked by major developments in governance, culture, and scientific exploration.

During this time, the Abbasids strengthened their control, implemented political reforms, and laid the foundation for the golden age of Islam, symbolized by the founding of Baghdad as the Capital, a center of learning, commerce, and innovations.

Abu al-Abbas as-Saffah (750–754 CE)

Abu al-Abbas Al-Saffah, the first Abbasid caliph, is known as “Al-Saffah,” meaning the Blood-Shedder. Abu al-Abbas established the Abbasid dynasty by overthrowing the Umayyad caliphate in a series of battles and revolts. They secured their rule over the Islamic world. After overthrowing the Umayyad dynasty, Al-Saffah focused on consolidating power, eliminating threats, and winning the loyalty of various Muslim communities. His efforts established the Abbasids as legitimate rulers, providing a strong start for the dynasty that would dominate the Islamic world for centuries.

Al-Mansur (754–775 CE)

Al-Mansur, the second Abbasid caliph, is widely regarded as the true architect of the Abbasid Caliphate. He is best known for founding Baghdad (round city) as the Capital in 762 CE, Positioned strategically along the Tigris River. Al-Mansur planned Baghdad as a hub of commerce, administration, and culture, designed to showcase the empire’s grandeur and centralize its governance. His administrative reforms and policies brought stability and organization to the Abbasid state, helping to create a thriving economy and a robust bureaucracy that would support the dynasty’s expansion and consolidation.

Al-Mahdi (775–785 CE)

Under Al-Mahdi, the Abbasid Caliphate enjoyed economic prosperity and cultural expansion. He invested in public works, including roads, canals, and mosques, and his reign saw greater engagement with scholars and artists. Al-Mahdi also faced early challenges from religious dissenters, such as the rise of the Zindīq (heretics), whom he actively persecuted for maintaining religious orthodoxy.

Al-Hadi (785–786 CE)

Although Al-Hadi’s reign was short, it was marked by internal family conflict and efforts to continue his father’s policies. He is known for trying to assert his authority over his brother Harun al-Rashid, creating tension within the Abbasid court. His sudden death brought an end to these conflicts, and his successor, Harun al-Rashid, ascended to power.

Harun al-Rashid (786–809 CE)

Harun al-Rashid was one of the most famous Abbasid caliphs. He fostered a culture of learning, literature, and science, making Baghdad the intellectual center of the Islamic world. His court in Baghdad was a vibrant center of learning, science, and the arts.

Harun al-Rashid is famously associated with the tales of One Thousand and One Nights, symbolizing the wealth and splendor of his reign. He also fostered relationships with other empires, such as the Byzantine Empire, through diplomacy and trade.

Al-Amin (809–813 CE)

Al-Amin’s reign was marked by a severe conflict with his half-brother, Al-Mamun. This fraternal rivalry erupted into a civil war known as the Fourth Fitna, which ultimately weakened the Abbasid Caliphate. Al-Amin’s defeat by Al-Mamun brought significant changes in the political structure and set the stage for a period of intellectual and cultural flourishing under Al-Mamun.

Al-Mamun (813–833 CE)

Al-Mamun, one of Harun al-Rashid’s sons, continued his father’s legacy of intellectual patronage. However, he is especially known for founding the Bayt al-Hikma, or the House of Wisdom, in Baghdad, where scholars of translation movement translated Greek, Persian, and Indian texts into Arabic. This institution became a leading center for translation, research, and scientific study, drawing scholars from various regions and backgrounds. His support for intellectual pursuits fostered advancements in fields like mathematics, astronomy, and philosophy, significantly contributing to the Islamic Golden Age. Al-Mamun also faced religious dissent and promoted the rationalist Mutazilite doctrine, an Islamic theological school that emphasized reason and rationalism, advocating for the unity and justice of God, leading to tension within the empire.

Al-Mutasim (833–842 CE)

Al-Mutasim is known for his military reforms, particularly his use of Turkish soldiers, which created a powerful army but also sowed seeds of future unrest. His establishment of the city of Samarra as a new capital was an effort to assert control over his troops and administration. His reign saw successful military campaigns against the Byzantine Empire, bolstering the Caliphate’s territorial strength.

Al-Wathiq (842–847 CE)

Al-Wathiq’s reign was marked by his continued support of the Mutazilite doctrine, which led to increased religious tension. He followed in his father’s footsteps, prioritizing military preparedness, particularly against the Byzantine Empire. Despite some achievements, his reign faced challenges due to growing unrest among factions within the Abbasid military.

Al-Mutawakkil (847–861 CE)

Al-Mutawakkil is often remembered for reversing the religious policies of his predecessors by rejecting Mutazilism and restoring Sunni orthodoxy. His reign was significant for its religious reforms and for halting the persecution of Sunni scholars. However, he faced severe internal challenges, particularly from the Turkish soldiers he inherited from Al-Mutasim’s reforms. This ultimately led to his assassination and marked the beginning of a turbulent period for the Abbasids.

2. Middle Abbasid Caliphs (861–945 CE)

The middle period of the Abbasid Caliphate saw increased political fragmentation as local rulers and military commanders gained more influence, challenging the authority of the caliphs in Baghdad. Despite these political difficulties, cultural and intellectual achievements continued, especially within regional centers of the Islamic world.

Al-Muntasir (861–862 CE)

Al-Muntasir’s reign was short and followed the turbulent assassination of his father, Al-Mutawakkil. His rule marked the beginning of a series of quick successions, largely controlled by powerful Turkish military leaders. Though brief, his reign signaled the diminishing power of the Caliphate as Turkish influence grew.

Al-Mustain (862–866 CE)

Placed on the throne by the Turkish commanders, Al-Mustain’s reign was marked by civil unrest and a power struggle with rival factions within Baghdad. His Caliphate ultimately ended when he was forced to abdicate in favor of his cousin, Al-Mu’tazz, and was later executed.

Al-Mutazz (866–869 CE)

Al-Mutazz attempted to reclaim authority over the military by resisting the Turkish commanders who had controlled his predecessors. Despite his efforts, his reign was marred by ongoing power struggles and financial troubles. He was eventually overthrown and killed by those same factions.

Al-Muhtadi (869–870 CE)

Known for his attempts to restore Islamic governance and reduce corruption, Al-Muhtadi tried to reform the Caliphate’s administration. However, his ideals conflicted with the interests of the powerful military factions, leading to his downfall and assassination within a year.

Al-Mutamid (870–892 CE)

Al-Mutamid’s lengthy reign brought some stability, largely due to his brother and powerful advisor, Al-Muwaffaq. Together, they managed to fend off external threats, like the Zanj Rebellion, a major slave revolt in southern Iraq. Although Al-Mutamid nominally held power, his brother Al-Muwaffaq acted as the de facto ruler, steering the empire through these crises.

Al-Mutadid (892–902 CE)

Al-Mutadid is remembered for his strong efforts to reassert Abbasid control over rebellious territories. He employed diplomacy and military force to bring areas like Egypt and parts of Iran back under central rule. His administrative reforms and attempts at financial recovery strengthened the Caliphate, although his policies placed a heavy burden on the treasury.

Al-Muktafi (902–908 CE)

Al-Muktafi’s reign was characterized by peace and relative prosperity. He successfully defended the Caliphate from the Qarmatians, a radical Ismaili Shia sect known for their revolutionary activities. He focused on maintaining stability within the empire. His efficient administration allowed for a temporary respite from the conflicts that had plagued previous caliphs.

Al-Muqtadir (908–932 CE)

Ascending to the throne at a young age, Al-Muqtadir’s reign is often considered the beginning of the Abbasid decline. His long rule was marked by a lack of centralized control, as powerful court officials and military leaders held real authority. Despite this, Baghdad continued to flourish as a center of learning and culture, even as political power slipped away.

Al-Qahir (932–934 CE)

Al-Qahir attempted to restore caliphal authority by taking a hard line against the powerful military commanders. His uncompromising approach led to his overthrow and imprisonment. Although his reign was brief, his efforts highlighted the caliphs’ ongoing struggle to reclaim power from the Turkish and Persian factions.

Al-Radi (934–940 CE)

Al-Radi is noted for formally recognizing the position of Amir al-Umara (Commander of Commanders), essentially creating a new office to handle military and administrative matters. This marked a significant shift, as the caliph was now largely symbolic, with real authority vested in the Amir al-Umara. This structural change further eroded the Caliphate’s central authority.

Al-Muttaqi (940–944 CE)

Al-Muttaqi’s reign saw ongoing instability, with constant power struggles and factional disputes. He fled Baghdad in an attempt to escape the control of the powerful military commanders but was eventually captured and blinded, ending his Caliphate in a brutal manner that underscored the Caliphate’s declining influence.

Al-Mustakfi (944–946 CE)

Al-Mustakfi ruled during a period of increasing control by the Buyid dynasty, a Shia Persian military family who would dominate Baghdad and the Abbasid caliphs. Al-Mustakfi’s brief reign ended when he was deposed and blinded by the Buyids, signaling the formal end of Abbasid independence in Baghdad.

3. Later Abbasid Caliphs (946–1258 CE)

The later Caliphs of the Abbasid dynasty were largely symbolic leaders as the dynasty faced internal challenges. Real power was often held by military commanders, Persian bureaucrats, and later, the Seljuks, A Turkish Sunni Muslim dynasty, and other foreign powers. Despite their diminished authority, the Abbasid caliphs continued to serve as religious and cultural figures, presiding over a period that saw significant intellectual and artistic achievements. This era ultimately came to an end with the Mongol invasion in 1258 CE.

Al-Muti (946–974 CE)

Al-Muti’s reign marked the beginning of Buyid control over Baghdad, as the Buyid dynasty, a Persian Shiite dynasty, dominated the Abbasid caliphs and exercised real power. Under Al-Muti, the Caliphate lost significant authority, and Baghdad came under direct Buyid rule. However, religious and cultural activities continued, as the Abbasid caliphs were still viewed as spiritual leaders.

Al-Tai (974–991 CE)

Al-Tai, a figurehead under Buyid’s influence, had minimal actual authority. He faced financial constraints, with much of the Caliphate’s wealth diverted to the Buyid rulers. Al-Ta’i was eventually deposed by the Buyids, who installed another caliph of their choice, further underscoring the Caliphate’s symbolic status.

Al-Qadir (991–1031 CE)

Al-Qadir’s long reign saw attempts to reassert Sunni orthodoxy in response to the Shiite influence of the Buyids. He commissioned works that promoted Sunni theology and denounced heretical views. Despite this, the Buyids continued to control the political aspects of the Caliphate, with Al-Qadir serving primarily as a religious leader.

Al-Qaim (1031–1075 CE)

Al-Qaim ruled during a time of increasing Seljuk influence. The Seljuk Turks, who were Sunni Muslims, began to gain power in Baghdad, eventually displacing the Buyids. Under the Seljuks, the Caliphate saw a revival of Sunni dominance, though the Abbasids remained figureheads.

Al-Muqtadi (1075–1094 CE)

Al-Muqtadi enjoyed somewhat more independence under the Seljuks, as the Seljuk sultans recognized the religious authority of the Caliphate while managing the political realm. During his reign, there was a cultural resurgence in Baghdad, with the establishment of institutions such as the Nizamiyya, an influential madrasa (school) for Sunni scholarship.

Al-Mustazhir (1094–1118 CE)

Al-Mustazhir’s reign saw the beginning of the Crusades, A series of medieval military campaigns launched by European Christians to reclaim the Holy Land from Muslim rule from 1096 to 1291 CE. Although the caliphs lacked the military power to resist the Crusaders directly, they served as symbols of Islamic unity, supporting leaders who resisted Crusader advances.

Al-Mustarshid (1118–1135 CE)

Known for his assertiveness, Al-Mustarshid attempted to reclaim some political authority, even engaging in military conflicts against the Seljuks. However, his efforts were ultimately unsuccessful, and he was killed in a Seljuk campaign. His reign represented one of the few attempts by a later Abbasid caliph to regain real power.

Al-Rashid (1135–1136 CE)

Al-Rashid’s short reign was marked by continued conflicts with the Seljuks. He was quickly deposed, marking a period of rapid succession and instability within the Abbasid caliphate, with political authority firmly in the hands of external powers.

Al-Muqtafi (1136–1160 CE)

Al-Muqtafi benefited from the temporary fragmentation of the Seljuk Empire, allowing him to gain a degree of independence in Baghdad. He managed to consolidate power within the city and defend it from regional threats, marking a rare period of relative autonomy for the Abbasid caliphs.

Al-Mustanjid (1160–1170 CE)

Al-Mustanjid continued his predecessor’s policy of limited autonomy within Baghdad, maintaining stability and focusing on domestic governance. Though he lacked substantial influence outside the city, Baghdad experienced a period of economic and cultural growth.

Al-Mustadi (1170–1180 CE)

Al-Mustadi’s reign was marked by further consolidation within Baghdad. He supported various public works, including improvements to mosques and educational institutions, reflecting a focus on strengthening the city’s infrastructure and spiritual life.

Al-Nasir (1180–1225 CE)

Al-Nasir is one of the few later Abbasid caliphs who managed to reclaim some influence beyond Baghdad. He maintained diplomatic relations and alliances, even involving himself in military affairs when possible. His reign saw efforts to unify the Islamic world, though these were limited by the Caliphate’s reduced power.

Al-Zahir (1225–1226 CE)

Al-Zahir’s brief reign involved limited achievements due to his short time in power. Baghdad continued to thrive as a cultural center, but his rule was largely uneventful.

Al-Mustansir (1226–1242 CE)

Known for establishing the prestigious Mustansiriya Madrasa, Al-Mustansir focused on Baghdad’s educational and cultural development. The madrasa became a renowned institution for Islamic learning, and his reign is remembered for these cultural contributions rather than political influence.

Al-Mustasim (1242–1258 CE)

Al-Mustasim was the last caliph of the Abbasid dynasty in Baghdad. His reign ended with the Mongol invasion led by Hulagu Khan. Despite appeals for support, Al-Mustasim could not rally a strong defense, and Baghdad was sacked in 1258, effectively ending the Abbasid Caliphate and its rule in the Islamic heartland.

Conclusion

The Abbasid Caliphate, spanning over five centuries from 750 to 1258 CE, left an enduring legacy on the Islamic world. The early caliphs, as detailed in the list of Abbasid caliphs, established a powerful and prosperous empire, fostering a golden age of Islamic civilization. However, as time passed, the Caliphate faced increasing challenges, including political instability, regional fragmentation, and external threats. The Mongol invasion of 1258 marked the end of the Abbasid dynasty. However, its cultural and intellectual contributions continue to inspire and shape the world today.

Frequently Asked Questions

What are the caliphs?

Caliphs are political and religious leaders in Islam, regarded as successors to the Prophet Muhammad. They serve as the heads of the Muslim community, or ummah, and are responsible for upholding Islamic laws, traditions, and governance.

How many Abbasid caliphs were there?

There were 37 Abbasid caliphs from the dynasty’s inception in 750 CE to its fall in 1258 CE.

How long did the Abbasid Caliphate rule?

The Abbasid Caliphate ruled for approximately 508 years, from 750 CE to 1258 CE.

Who was the first caliph of the Abbasid dynasty?

The first caliph of the Abbasid dynasty was Abu al-Abbas as-Saffah, who ruled from 750 to 754 CE.

Who was the last caliph of the Abbasid dynasty?

The last caliph of the Abbasid dynasty was Al-Mustasim, whose reign ended with the Mongol invasion in 1258 CE.

References:

- Philip Khuri Hitti. History of the Arabs: From the Earliest Times to the Present.

- Tayeb El-Hibri. The Abbasid Caliphate: A History

- Kennedy, Hugh. The early Abbasid Caliphate: a political history

- Ibn al-Athir. Al-Kamil fi al-Tarikh (The Complete History).

- William Muir. The Caliphate: Its Rise, Decline and Fall from Original Sources

- M. A. Shaban. The ‘Abbāsid Revolution

Wikipedia