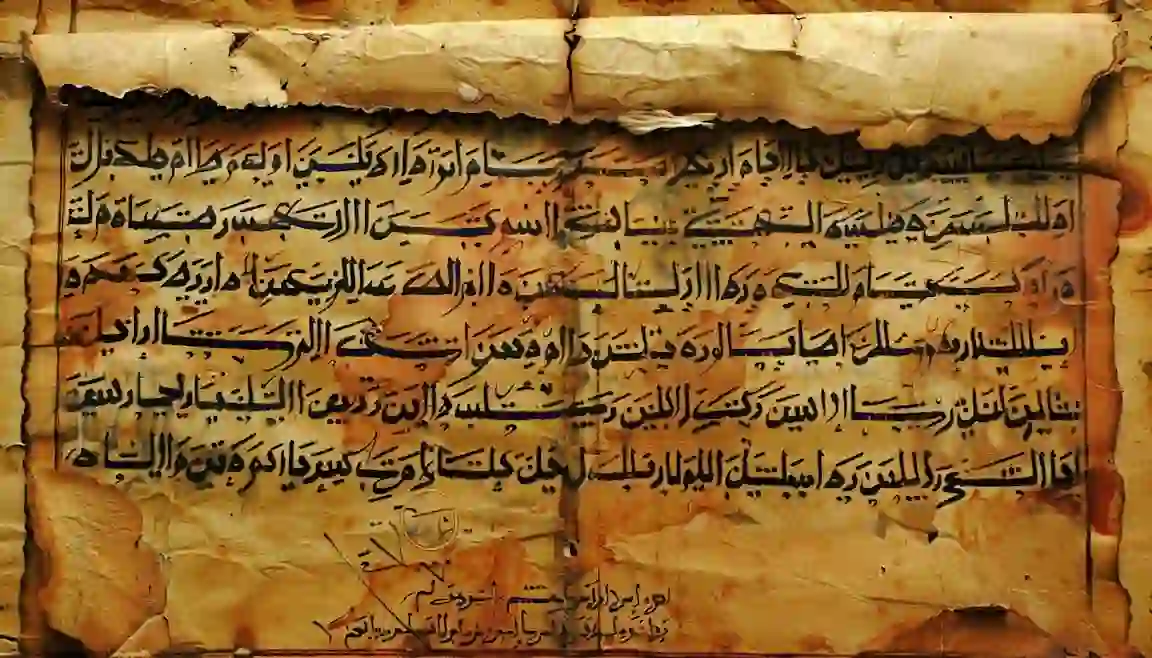

The Charter of Madina, also known as the Constitution of Madina (دستور المدينة, Dustūr al-Madīna) or the Treaty of Madina, was a constitutional document drafted by the Prophet Muhammad (Peace Be Upon Him) in 622 CE (1 A.H.). This groundbreaking Charter was established to regulate the relations between the diverse population of Madina (then Yathrib), which included Muslims, Jews, Christians, and pagan tribes.

It laid down a comprehensive framework for governance, justice, and social welfare, ensuring that all communities could coexist peacefully under a unified legal system. The Charter of Madina established the foundation for the first Islamic state in Madina and set a precedent for modern-day constitutional governance.

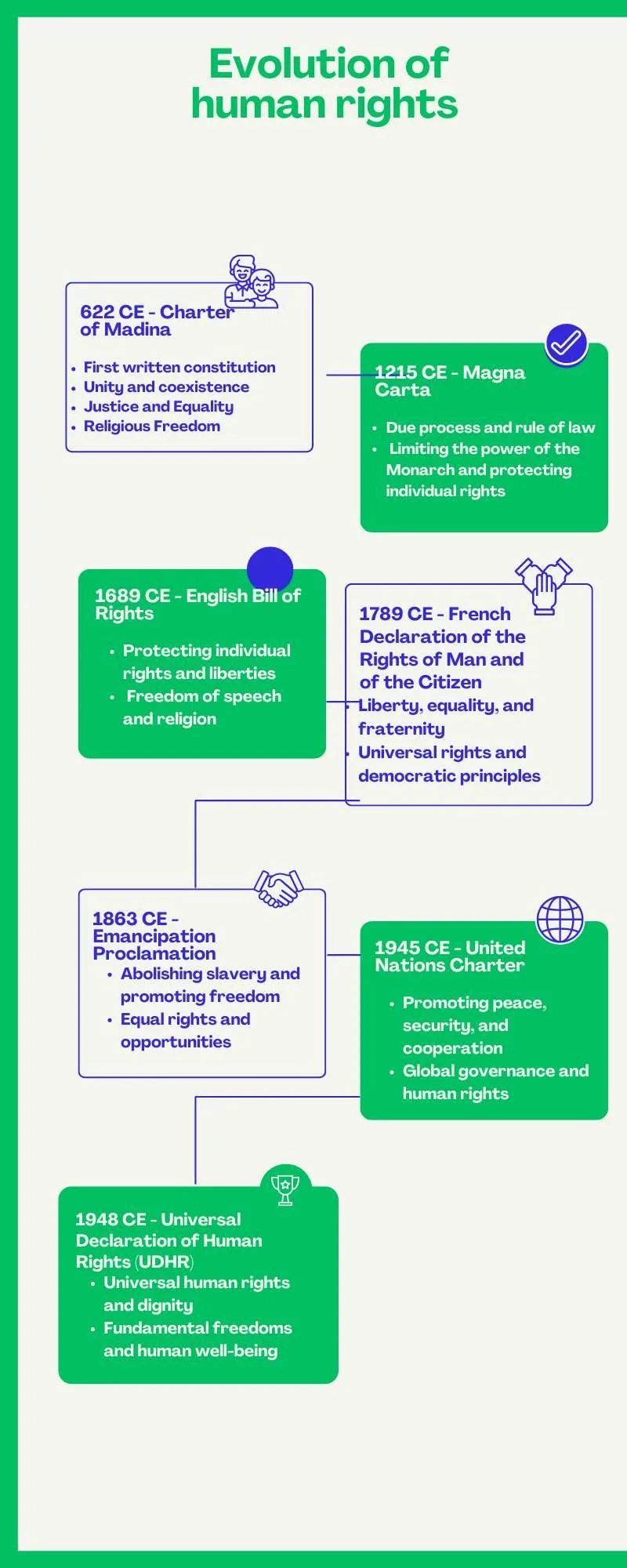

The Madina Charter is considered one of the earliest examples of a written constitution in history. It predates the Magna Carta (1215 CE) by almost six centuries and established a framework for governance based on principles of justice, tolerance, and mutual respect.

This article aims to provide a thorough understanding of the Charter of Madina, its historical context, and its enduring relevance in contemporary society. By exploring its articles, significance, and impact on international relations, diplomacy, and human rights, readers will gain a comprehensive insight into this pivotal document and its contributions to forming the first Islamic state.

Historical Context

Background of Charter of Madina

To truly understand the significance of the Charter of Madina, it is essential to delve into its historical context.

The Situation in Medina (Yathrib) Before the Charter

Before the arrival of Prophet Muhammad (PBUH) and his followers, Madina (then Yathrib) was a city plagued by intense tribal conflicts and social discord. The city was predominantly inhabited by two major Arab tribes, Banu Aus and Banu Khazraj, who were embroiled in a bitter and longstanding feud marked by cycles of violence and retaliation that destabilized the community.

In addition to the Arab tribes, Yathrib was home to several Jewish tribes, including the Banu Qaynuqa, Banu Nadir, and Banu Qurayza. These Jewish tribes had their own social systems, religious practices, and political structures. Although significant players in the city’s economy and politics, they were not immune to the overarching tribal conflicts that defined Yathrib’s social dynamics.

The city’s social and political climate was further complicated by various pagan tribes, each with its own beliefs and practices. The frequent skirmishes and shifting alliances among these groups created a volatile environment, making it difficult to establish lasting peace and stability.

The social and political climate of Medina was marked by:

- Inter-tribal conflicts: The Banu Aus and Banu Khazraj had been at odds for over 100 years, with frequent battles and bloodshed.

- Jewish-Arab tensions: The Jewish community lived in uneasy tension with the Arab tribes, with occasional skirmishes and disputes.

- Political fragmentation: Medina was a city without a central authority, with each tribe and community operating independently.

Historical Circumstances Leading Up to the Drafting of the Charter

The Hijra, the migration of Prophet Muhammad (PBUH) and his followers from Mecca to Medina in 622 CE (1 A.H.) was a turning point in Islamic history. This migration was driven by increasing persecution and hostility faced by Muslims in Mecca and upon their arrival in Medina, the Prophet Muhammad (PBUH) faced the challenge of uniting a diverse and fractured community.

The need for a unifying document became apparent as the Prophet sought to establish a stable and harmonious society in Medina. Thus, the Charter of Medina was drafted in 622 CE (1 A.H.) as a constitutional document to regulate relations among the various factions, ensure justice, and foster mutual respect and cooperation.

According to historical accounts, the Charter of Medina was written by Ali ibn Abi Talib, a cousin and son-in-law of Prophet Muhammad (PBUH). Ali was known for his literacy and was often called upon to write important documents on behalf of the Prophet. Reports indicate that Ali wrote down the terms of the Charter as Prophet Muhammad (PBUH) dictated them. This process was likely done in the presence of other witnesses, including the leaders of the various tribes and communities mentioned in the Charter.

Formation of the Community in Medina

Need for Establishing a Peaceful and Unified Society in Medina

With the arrival of Prophet Muhammad (PBUH) and the Muhajirun (emigrants from Mecca), Medina’s social landscape changed significantly. The Prophet recognized the necessity of creating a cohesive community where the rights and duties of all individuals were clearly defined and respected. Establishing a peaceful and unified society was crucial not only for the survival of the Muslim community but also for the overall stability and prosperity of Medina.

The Diverse Groups Living in Medina at the Time

The population of Medina at the time was a mosaic of different groups, each with its own unique identity and interests. These groups included:

- Muslims (Muhajirun and Ansar): The early converts to Islam comprised the Muhajirun, who had emigrated from Mecca, and the Ansar, the native inhabitants of Medina who had embraced Islam and pledged their support to Prophet Muhammad (PBUH).

- Jewish Tribes: The Jewish tribes, who had settled in Medina after the Roman destruction of Jerusalem in 70 C.E., lived in uneasy tension with the Arab tribes, including the Banu Qaynuqa, Banu Nadir, and Banu Qurayza. They played a significant role in the city’s economic and political life and had their own social and religious structures.

- Arab Tribes: Banu Aus and Banu Khazraj were prominent Arab tribes and smaller Arab groups, each with their own leadership and customs.

- Pagan Tribes: Various pagan Arab tribes, with their traditional beliefs and practices, also resided in Medina. Their presence added to the city’s cultural and religious diversity.

- Christian and Other Minorities: Although less numerous, Christians and other religious minorities also lived in Medina.

Here are the names of the Jewish tribes that were settled in Madina at the time, in both English and Urdu:

- Banu Qaynuqa (بنو قینقاع)

- Banu Nadir (بنو نضیر)

- Banu Qurayza (بنو قریظہ)

- Banu Harith (بنو حارث)

- Banu Jusham (بنو جشم)

- Banu Tha’laba (بنو ثعلبہ)

- Banu Awf (بنو عوف)

- Banu Najjar (بنو نجار)

- Banu Shatba (بنو شطیبہ)

- Banu Al-Aus (بنو اوس)

The Charter of Medina aimed to create a social contract to ensure justice, security, and cooperation among these diverse groups, laying the groundwork for a unified and peaceful society.

Detailed Examination of the Charter

The Charter of Medina was a powerful and comprehensive agreement, though not a lengthy document by modern standards.

Note:

- In Islamic scholarship and Arabic literature, the city is commonly written as “Madina” (مدينة), which is the Arabic pronunciation.

- In Western scholarship and English literature, the city is commonly written as “Medina”, the Latinised version of the name.

- Ummat is an Arabic term that translates to “nation,” “community,” or “people.” In the Islamic context, it often refers to the entire Muslim community worldwide, transcending geographical boundaries.

- Mawla is an Arabic term that has multiple meanings. In the context of the Charter of Medina, it generally refers to a freed slave, a client, or a protégé. It signifies a special relationship between individuals, where one person offers protection and support to another.

- Charter of Madina (Masiqa e Madina in urdu)

Charter of Madina Articles

The exact number of articles in the Charter of Madina varies depending on the source. However, it’s generally estimated to be around 47-62 articles. These articles were structured as a series of agreements and stipulations addressing various aspects of communal life.

According to the sources that determined the Charter of Madina total articles 47, the Charter of Medina comprises 47 articles, each addressing different aspects of governance, social relations, and justice within the newly formed community. These articles are systematically structured to cover various domains, including the rights and duties of the citizens, conflict resolution mechanisms, and the collective responsibility of maintaining peace and security.

Here is the translation of the Charter of Madina by Dr. Muhammad Hamidullah, a renowned Islamic scholar and historian born in 1908 in Hyderabad, India. He contributed significantly to Islamic research, notably translating and analyzing key Islamic texts. His scholarly works, including the translation of the Charter of Madina, are highly respected for their academic rigour and insight into Islamic law and history.

In the name of God, the Beneficent and the Merciful.

- This is a prescript of Muhammad (صلى الله عليه وسلم), the Prophet and Messenger of God (to operate) between the faithful and the followers of Islam from among the Quraish and the people of Madina and those who may be under them, may join them and take part in wars in their company.

- They shall constitute a separate political unit (Ummat) as distinguished from all the people (of the world).

- The emigrants from the Quraish shall be (responsible) for their own ward; and shall pay their blood-money in mutual collaboration and shall secure the release of their own prisoners by paying their ransom from themselves, so that the mutual dealings between the believers be in accordance with the principles of goodness and justice..

- And Banu ‘Awf shall be responsible for their own ward and shall pay their blood-money in mutual collaboration, and every group shall secure the release of its own prisoners by paying their ransom from themselves so that the dealings between the believers be in accordance with the principles of goodness and justice.

- And Banu Al-Harith-ibn-Khazraj shall be responsible for their own ward and shall pay their blood-money in mutual collaboration and every group shall secure the release of its own prisoners by paying their ransom from themselves, so that the dealings between the believers be in accordance with the principles of goodness and justice.

- And Banu Sa‘ida shall be responsible for their own ward, and shall pay their blood-money in mutual collaboration and every group shall secure the release of its own prisoners by paying their ransom from themselves, so that the dealings between the believers be in accordance with the principles of goodness and justice.

- And Banu Jusham shall be responsible for their own ward and shall pay their blood-money in mutual collaboration and every group shall secure the release of its own prisoners by paying their ransom so that the dealings between the believers be in accordance with the principles of goodness and justice.

- And Banu an-Najjar shall be responsible for their own ward and shall pay their blood-money in mutual collaboration and every group shall secure the release of its own prisoners by paying their ransom so that the dealings between the believers be in accordance with the principles of goodness and justice.

- And Banu ‘Amr-ibn-‘Awf shall be responsible for their own ward and shall pay their blood-money in mutual collaboration and every group shall secure the release of its own prisoners by paying their ransom, so that the dealings between the believers be in accordance with the principles of goodness and justice.

- And Banu-al-Nabit shall be responsible for their own ward and shall pay their blood-money in mutual collaboration and every group shall secure the release of its own prisoners by paying their ransom so that the dealings between the believers be in accordance with the principles of goodness and justice.

- And Banu-al-Aws shall be responsible for their own ward and shall pay their blood-money in mutual collaboration and every group shall secure the release of its own prisoners by paying their ransom, so that the dealings between the believers be in accordance with the principles of goodness and justice.

- (a) And the believers shall not leave any one, hard-pressed with debts, without affording him some relief, in order that the dealings between the believers be in accordance with the principles of goodness and justice.

(b) Also no believer shall enter into a contract of clientage with one who is already in such a contract with another believer. - And the hands of pious believers shall be raised against every such person as rises in rebellion or attempts to acquire anything by force or is guilty of any sin or excess or attempts to spread mischief among the believers ; their hands shall be raised all together against such a person, even if he be a son to any one of them.

- And no believer shall kill another believer in retaliation for an unbeliever, nor shall he help an unbeliever against a believer.

- And the protection of God is one. The humblest of them (believers) can, by extending his pro-tection to any one, put the obligation on all; and the believers are brothers to one another as against all the people (of the world).

- And that those who will obey us among the Jews, will have help and equality. Neither shall they be oppressed nor will any help be given against them.

- And the peace of the believers shall be one. If there be any war in the way of God, no believer shall be under any peace (with the enemy) apart from other believers, unless it (this peace) be the same and equally binding on all.

- And all those detachments that will fight on our side will be relieved by turns.

- And the believers as a body shall take blood vengeance in the way of God.

- (a) And undoubtedly pious believers are the best and in the rightest course.

(b) And that no associator (non-Muslim subject) ahall give any protection to the life and property of a Quraishite, nor shall he come in the way of any believer in this matter.. - And if any one intentionally murders a believer, and it is proved, he shall be killed in retaliation, unless the heir of the murdered person be satisfied with blood-money. And all believers shall actually stand for this ordinance and nothing else shall be proper for them to do.

- And it shall not be lawful for any one, who has agreed to carry out the provisions laid down in this code and has affixed his faith in God and the Day of Judgment, to give help or protection to any murderer, and if he gives any help or protection to such a person, God‟s curse and wrath shall be on him on the Day of Resurrection, and no money or compensation shall be accepted from such a person.

- And that whenever you differ about anything, refer it to God and to Muhammad (صلى الله عليه وسلم).

- And the Jews shall share with the believers the expenses of war so long as they fight in conjunction,

- And the Jews of Banu ‘Awf shall be considered as one political community (Ummat) along with the believers—for the Jews their religion, and for the Muslims theirs, be one client or patron. He, however, who is guilty of oppression or breach of treaty, shall suffer the resultant trouble as also his family, but no one besides.

- And the Jews of Banu-an-Najjar shall have the same rights as the Jews of Banu ‘Awf.

- And the Jews of Banu-al-Harith shall have the same rights as the Jews of Banu ‘Awf.

- And the Jews of Banu Sa‘ida shall have the same rights as the Jews of Banu ‘Awf

- And the Jews of Banu Jusham shall have the same rights as the Jews of Banu ‘Awf.

- And the Jews of Banu al-Aws shall have the same rights as the Jews of Banu ‘Awf.

- And the Jews of Banu Tha‘laba shall have the same rights as the Jews of Banu ‘Awf. Of course, whoever is found guilty of oppression or violation of treaty, shall himself suffer the consequent trouble as also his family, but no one besides.

- And Jafna, who are a branch of the Tha’laba tribe, shall have the same rights as the mother tribes.

- And Banu-ash-Shutaiba shall have the same rights as the Jews of Banu ‘Awf ; and they shall be faithful to, and not violators of, treaty.

- And the mawlas (clients) of Tha’laba shall have the same rights as those of the original members of it.

- And the sub-branches of the Jewish tribes shall have the same rights as the mother tribes.

- (a) And that none of them shall go out to fight as a soldier of the Muslim army, without the per-mission of Muhammad (صلى الله عليه وسلم).

(b) And no obstruction shall be placed in the way of any one‟s retaliation for beating or injuries; and whoever sheds blood shall be personally responsible for it as well as his family; or else (i.e., any step beyond this) will be of oppression; and God will be with him who will most faithfully follow this code (sahifdh) in action. - (a) And the Jews shall bear the burden of their expenses and the Muslims theirs.

(b) And if any one fights against the people of this code, their (i.e., of the Jews and Muslims) mutual help shall come into operation, and there shall be friendly counsel and sincere behaviour between them; and faithfulness and no breach of covenant. - And the Jews shall be bearing their own expenses so long as they shall be fighting in conjunction with the believers.

- And the Valley of Yathrib (Madina) shall be a Haram (sacred place) for the people of this code.

- The clients (mawla) shall have the same treatment as the original persons (i.e., persons accepting clientage). He shall neither be harmed nor shall he himself break the covenant.

- And no refuge shall be given to any one without the permission of the people of the place (i.e., the refugee shall have no right of giving refuge to others).

- And that if any murder or quarrel takes place among the people of this code, from which any trouble may be feared, it shall be referred to God and God‟s Messenger, Muhammad (صلى الله عليه وسلم) ;and God will be with him who will be most particular about what is written in this code and act on it most faithfully.

- The Quraish shall be given no protection nor shall they who help them.

- And they (i.e., Jews and Muslims) shall have each other‟s help in the event of any one invading Yathrib.

- (a) And if they (i.e., the Jews) are invited to any peace, they also shall offer peace and shall be a party to it; and if they invite the believers to some such affairs, it shall be their (Muslims) duty as well to reciprocate the dealings, excepting that any one makes a religious war.

(b) On every group shall rest the responsibility of (repulsing) the enemy from the place which faces its part of the city. - And the Jews of the tribe of al-Aws, clients as well as original members, shall have the same rights as the people of this code: and shall behave sincerely and faithfully towards the latter, not perpetrating any breach of covenant. As one shall sow so shall he reap. And God is with him who will most sincerely and faithfully carry out the provisions of this code.

- And this prescript shall not be of any avail to any oppressor or breaker of covenant. And one shall have security whether one goes out to a campaign or remains in Madina, or else it will be an oppression and breach of covenant. And God is the Protector of him who performs the obligations with faithfulness and care, as also His Messenger Muhammad (صلى الله عليه وسلم).

For those interested in reading the original work, Dr. Hamidullah’s book ‘The First Written Constitution of the World’ can be accessed here THE FIRST WRITTEN CONSTITUTION OF THE WORLD

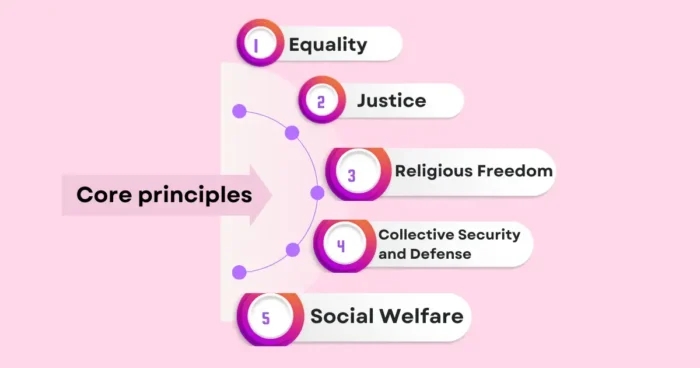

Main points of Charter of Madina

Highlighting the Main Points and Principles:

- Recognition of the Prophet’s Leadership: The Charter acknowledged Prophet Muhammad as the Muslim community leader (Ummah).

- Unity and Solidarity: The Charter emphasised the importance of unity among the Muslim community and the necessity of mutual support and cooperation.

- Justice and Equality: It established principles of justice and equality, ensuring that all community members, regardless of their background, were treated fairly.

- Religious Freedom: The Charter guaranteed religious freedom for all inhabitants, allowing Jews and non-Muslims to practice their faith without interference.

- Mutual Defence: It outlined the collective responsibility of defending Medina from external threats, promoting a sense of shared security.

- Conflict Resolution: The Charter provided mechanisms for resolving disputes and conflicts within the community, ensuring that justice prevailed.

Significance at the Time and Lasting Impact

- Significance at the Time: The Charter was revolutionary in its inclusivity and its approach to governance. It united diverse groups under a single legal framework, promoting peace and stability in a historically volatile region.

- Lasting Impact: The principles enshrined in the Charter have had a lasting impact on Islamic governance and law. Its emphasis on justice, equality, and religious freedom inspires modern legal and social systems, highlighting its enduring relevance.

Members of the Charter of Medina

List of Signatories:

- Muslims: The Prophet Muhammad (Leader and arbiter) and other key leaders from the Muhajirun and Ansar.

- Jews: Representatives from the Jewish tribes of Banu Qaynuqa, Banu Nadir, and Banu Qurayza.

- Leaders of the Arab tribes: Representatives from Banu Aus and Banu Khazraj.

- Others: Leaders from various pagan and other minority groups residing in Medina.

Roles and Responsibilities of Each Group:

- Muslims: The Muslims were responsible for upholding the principles of Islam, ensuring justice, and defending the community. They also played a crucial role in supporting the Prophet Muhammad (PBUH) in his leadership.

- Jews: The Jewish tribes were guaranteed religious freedom and autonomy in their internal affairs. They were also responsible for contributing to the defence of Medina and maintaining peaceful relations with the Muslims.

- Arab Tribes: Ending their internal conflicts and participating in the governance of the new community.

- Others: The pagan and minority groups were also granted protection and religious freedom. They were expected to contribute to the collective security and abide by the laws established in the Charter.

Key Provisions and Principles

salient features of the Madina Charter

- Unity of the Ummah: The Charter established the Muslim community (Ummah) as a single entity, transcending tribal affiliations and fostering a collective identity.

- Collective Responsibility: It mandated collective responsibility for security and defence, requiring all groups to contribute to the protection of Medina.

- Justice and Fairness: The Charter emphasised justice and fairness, providing mechanisms for conflict resolution and ensuring that all members were treated equitably.

- Religious Freedom: It guaranteed religious freedom for all inhabitants, allowing Jews and other non-Muslims to practice their faith without interference.

- Mutual Support: It promoted mutual support and cooperation among the diverse groups, emphasizing the importance of assisting one another in times of need.

- Peaceful Coexistence: The Charter aimed to foster peaceful coexistence, prohibiting acts of treachery and ensuring that disputes were resolved through arbitration rather than violence.

Unique Aspects of the Charter:

- Inclusivity: The Charter was inclusive, recognising and respecting the rights of all inhabitants, regardless of their religious or tribal affiliations.

- Legal Framework: It provided a comprehensive legal framework that addressed various aspects of governance, social relations, and justice.

- Early Constitutional Document: As one of the earliest known constitutions, it set a precedent for developing legal and political systems in the Islamic world and beyond.

Significance in Promoting Peace and Coexistence

The Charter’s provisions were instrumental in creating a peaceful and stable environment in Medina. It facilitated:

- Resolution of Conflicts: The Charter helped curb inter-communal violence by establishing a framework for resolving disputes peacefully through mediation and arbitration.

- Security and Stability: The collective defence pact deterred external aggression, allowing the diverse communities of Medina to thrive.

- Social Cohesion: The Charter fostered a sense of shared identity and belonging within the Ummah, promoting social cohesion among different groups.

Charter of Madina and Human Rights

The Charter of Medina, though drafted centuries before the concept of codified human rights, contains several principles that resonate with modern human rights standards:

- Equality: The Charter emphasised the equality of all community members, regardless of their religious or tribal affiliations.

- Justice: It established mechanisms for ensuring justice, providing a framework for resolving disputes and protecting the rights of all individuals.

- Freedom of Religion: The Charter guaranteed religious freedom, allowing all inhabitants to practice their faith without interference.

- Protection of the Vulnerable: It included provisions for protecting society’s vulnerable members and ensuring their safety and well-being.

Comparison with Modern Human Rights Standards

While the Charter of Madina predates modern human rights conventions, its principles align closely with many contemporary human rights standards. The Charter’s emphasis on equality, justice, and religious freedom resonates with the values enshrined in modern human rights documents such as the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR).

Charter’s Influence on the Development of Human Rights

The Charter of Madina has had a lasting influence on the development of human rights within the Islamic tradition. Its principles have informed Islamic legal and ethical thought, contributing to the Muslim world’s broader discourse on human rights. The Charter’s emphasis on justice, equality, and protection of rights continues to inspire contemporary efforts to promote human rights and social justice.

The Charter of Medina’s emphasis on justice, equality, and religious freedom resonates with the core principles of modern human rights. To fully appreciate its influence, it’s essential to examine how these principles align with Islamic legal and ethical frameworks. Concepts such as ijtihad (independent legal reasoning), shura (consultation), and maslaha (public interest) offer valuable lenses for understanding the Charter’s impact. For instance, the Charter’s call for justice is an early articulation of the Islamic legal principle of adl (equity), which has been central to Islamic jurisprudence.

Relevance in Contemporary Times

The principles enshrined in the Charter of Madina remain highly relevant in contemporary times. In an increasingly diverse and interconnected world, the Charter’s emphasis on unity, justice, and mutual respect provides valuable insights for fostering peaceful coexistence and social harmony. Its focus on collective responsibility and protection of rights serves as a model for addressing modern challenges related to governance, social justice, and human rights.

The Charter of Medina’s principles offer valuable insights for addressing contemporary challenges. For example, its emphasis on unity and cooperation can inform strategies for promoting social cohesion in diverse societies. The Charter’s call for justice and equality can inspire policies to reduce inequality and discrimination. By drawing on the Charter’s wisdom, policymakers and community leaders can develop innovative approaches to pressing global issues.

Significance and Importance of the Charter of Medina

the Charter of Madina’s diplomatic importance

The Charter’s Role in Diplomacy and Inter-Community Relations: The Charter of Medina played a pivotal role in establishing a framework for diplomacy and inter-community relations. By creating a social contract that acknowledged and respected the diverse groups within Medina, the Charter set a precedent for peaceful coexistence and mutual cooperation. It facilitated dialogue and negotiation between different factions, fostering an environment where conflicts could be resolved through arbitration rather than violence.

Facilitation of Peaceful Coexistence and Precedents for Future Treaties

The Charter’s inclusive approach and emphasis on justice and equality laid the groundwork for future treaties and agreements. It demonstrated that diverse communities could coexist peacefully under a shared legal and ethical framework. This approach was revolutionary for its time and served as a model for subsequent diplomatic efforts both within the Islamic world and beyond.

Impact on International Relations and Diplomacy

The principles enshrined in the Charter influenced the development of diplomatic norms and practices in the early Islamic state. By promoting mutual respect, religious freedom, and collective security, the Charter helped to stabilise Medina and establish it as a centre of political and social order. Its impact extended to international relations, where similar principles were adopted in treaties and agreements between Muslim and non-Muslim states.

Lessons Learned for Modern Diplomatic Efforts

Modern diplomatic efforts can draw valuable lessons from the Charter of Medina. Its emphasis on inclusivity, justice, and mutual respect provides a robust foundation for resolving contemporary conflicts and fostering international cooperation. The Charter’s success in uniting diverse groups under a common framework underscores the importance of dialogue, negotiation, and respect for diversity in achieving lasting peace.

Political Implications

Establishing a New Form of Political Organisation

The Medina Charter established a new form of political organisation that combined religious and social elements. It created a unified community (Ummah) that transcended tribal affiliations and provided a cohesive governance structure. This new political entity was based on the principles of justice, mutual responsibility, and collective security, which were rooted in Islamic teachings.

Security and Stability

The Charter promoted security and stability in Medina by defining clear roles and responsibilities for all community members. It established mechanisms for conflict resolution and collective defence, reducing internal strife and external threats. The resulting stability attracted more people to the city, fostering economic growth and transforming Medina into a thriving centre of trade and culture.

Foundation of Statehood

Foundation for the First Islamic State

The Charter of Medina can be viewed as the foundation for the first Islamic state. It established essential elements of statehood, including a defined territory, a governed population, and a legal framework. The Charter’s principles of justice, equality, and collective responsibility laid the groundwork for the governance of the nascent Muslim community and set the stage for the expansion of the Islamic state.

Elements of Statehood Established by the Document:

- Defined Territory: The Charter delineated the boundaries of the community and established Medina as the centre of the new state.

- Governed Population: It acknowledged the diverse groups within Medina as part of a single community, united under the leadership of the Prophet Muhammad (PBUH).

- Legal Framework: The Charter provided a comprehensive legal and ethical framework for governance, addressing various aspects of social and political life.

Law and Governance

Groundwork for a Legal and Governance System

The Charter laid the groundwork for a legal and governance system in the nascent Muslim community. It established principles of justice, conflict resolution, and collective responsibility that informed the development of Islamic law (Sharia) and governance. These principles continue to influence Islamic legal and political thought to this day.

Historical Significance in Islamic History

The Medina Charter holds immense historical significance in Islamic history for several reasons:

- Establishing a Just Society: It laid the foundation for a society governed by Islamic principles of justice, tolerance, and social responsibility.

- Model for Governance: The Charter served as a model for future Islamic governments, emphasising consultation and the rule of law.

- Interfaith Relations: The Charter’s emphasis on religious freedom and peaceful coexistence with non-Muslims continues to influence Islamic perspectives on interfaith relations.

Lessons Learned for Modern Conflict Resolution

Modern conflict resolution can benefit from the lessons learned from the Charter of Medina. Its emphasis on justice, equality, and mutual respect provides a timeless framework for addressing conflicts and fostering peace. The Charter’s success in uniting diverse groups under a common legal and ethical framework underscores the importance of inclusivity and dialogue in achieving lasting solutions to contemporary conflicts.

- The Charter teaches us about mediation, compromise, and the value of written agreements.

- Its principles of conflict resolution remain relevant for addressing contemporary conflicts.

Modern Relevance

Legacy of the Charter of Madina

The principles of the Charter of Madina, such as justice, equality, and religious freedom, continue to be highly relevant today. These principles are echoed in various international human rights frameworks and legal systems. The Charter’s emphasis on inclusivity and mutual respect remains a powerful example for modern societies striving for peace and coexistence among diverse populations.

- Justice and Equality: The Charter’s commitment to justice and equality resonates with modern legal systems that aim to protect individual rights and ensure fair treatment for all.

- Religious Freedom: Its guarantee of religious freedom aligns with contemporary efforts to protect and promote the rights of religious minorities globally.

- Collective Responsibility: The concept of collective responsibility for community welfare is reflected in modern social contracts and community-based governance models.

Contemporary Interpretations

Modern Interpretations and Applications

Scholars and policymakers today interpret the Charter of Madina in various ways to address current social and political challenges. These interpretations often focus on how the Charter’s principles can inform modern governance, human rights, and interfaith dialogue.

- Governance: Modern interpretations highlight the Charter’s potential as a model for inclusive and participatory governance, promoting the idea that diverse groups can coexist under a shared legal framework.

- Human Rights: The Charter is often cited in discussions on Islamic perspectives on human rights, emphasizing its role in promoting justice, equality, and the protection of minority rights.

- Interfaith Dialogue: The principles of mutual respect and religious freedom enshrined in the Charter foster interfaith dialogue and cooperation, encouraging peaceful coexistence in multi-religious societies.

The Charter’s Enduring Relevance in the 21st Century

The Madina Charter offers invaluable insights into addressing the complex challenges of the 21st Century. Its emphasis on peace, justice, and cooperation remains highly relevant in a world marked by increasing interconnectedness and interdependence. For instance, the Charter’s model of interfaith harmony can serve as a blueprint for fostering understanding and respect among different religious communities. Furthermore, the document’s focus on collective responsibility can inspire innovative approaches to global challenges such as climate change and inequality. By drawing on the wisdom of the Charter, we can work towards a more just, equitable, and sustainable future.

Comparative Analysis

Comparison to Other Historical Documents and Treaties

The Charter of Madina can be compared to other significant historical documents and treaties that have shaped the course of human history. These comparisons highlight its unique contributions and enduring relevance.

- Magna Carta (1215): Like the Charter of Madina, the Magna Carta established principles of justice and the rule of law, influencing the development of legal and political systems in the West.

- Treaty of Westphalia (1648): The Treaty of Westphalia ended the Thirty Years’ War in Europe and emphasised the importance of state sovereignty and religious tolerance, similar to the Charter’s principles of autonomy and religious freedom.

- Universal Declaration of Human Rights (1948): The UDHR enshrines principles of justice, equality, and human rights, reflecting the foundational values of the Charter of Madina.

Impact on International Relations and Diplomacy

The Charter of Madina has had a lasting impact on international relations and diplomacy principles and practices. Its emphasis on justice, mutual respect, and peaceful coexistence continues to inform diplomatic efforts and international agreements.

- Justice and Fairness: The Charter’s principles of justice and fairness underpin modern diplomatic practices that seek equitable solutions to international conflicts.

- Mutual Respect: The Charter’s emphasis on mutual respect and recognition of diversity resonates with contemporary efforts to promote tolerance and understanding between nations and cultures.

- Peaceful Coexistence: Its model of peaceful coexistence serves as a valuable example for modern peacebuilding initiatives and conflict resolution strategies.

Lessons Learned for Modern Diplomatic Efforts

Modern diplomatic efforts can draw several lessons from the Charter of Madina:

- Inclusivity: Effective diplomacy requires the inclusion and participation of all stakeholders, mirroring the Charter’s inclusive approach.

- Dialogue and Negotiation: The Charter’s success in fostering peaceful coexistence through dialogue and negotiation underscores the importance of these tools in resolving contemporary conflicts.

- Respect for Diversity: Respecting and protecting the rights of diverse groups is crucial for maintaining peace and stability, as demonstrated by the Charter’s principles.

Conclusion

The Charter of Madina remains a remarkable document, demonstrating the power of unity, justice, and coexistence. Its principles inspire modern governance, human rights frameworks, and diplomatic efforts.

Understanding the Charter in its historical context allows us to appreciate its pioneering approach to creating a peaceful and inclusive society. The enduring importance of the Charter of Madina lies in its ability to offer timeless wisdom for addressing contemporary challenges related to diversity, conflict resolution, and social harmony.

Frequently Asked Questions

1. How many articles in charter of Madina?

The exact number of articles in the Charter of Medina is debated, with estimates ranging from 47 to 62. However, the most widely accepted figure is 47 articles.

2. What is the charter of Madina?

The Charter of Medina was a constitutional document drafted by Prophet Muhammad (PBUH) in 622 CE (1 A.H). It established a framework for governance, justice, and social welfare among the diverse population of Medina, including Muslims, Jews, Christians, and pagan tribes.

3. When was the charter of Madina made?

The Charter of Medina was drafted in 622 CE (1 A.H).

4. Who was chief signatory from Jews in charter of Madina?

There isn’t a specific “chief signatory” mentioned in historical records from the Jewish community. The Charter involved representatives from various Jewish tribes in Medina.

5. Who was from Jews in charter of Madina?

Several Jewish tribes were involved in the Charter of Medina, including the Banu Qaynuqa, Banu Nadir, and Banu Qurayza.

6. Who write articles in charter of Madina?

The Charter of Medina was written down by Ali ibn Abi Talib, a cousin and son-in-law of Prophet Muhammad (PBUH), as dictated by the Prophet.

7. What was the number of clauses of Charter of Madina?

The number of clauses is similar to the number of articles, which is estimated to be around 47-62.

8. What was the significance of the Medina charter?

The Charter of Medina was significant because it established a model for a multi-religious and multicultural society, emphasising justice, equality, and cooperation. It laid the foundation for the first Islamic state and influenced subsequent governance and legal systems.

9. Who were the members of Charter of Medina?

The members of the Charter of Medina included Muslims (Muhajirun and Ansar), Jewish tribes, Arab tribes, and other minority groups residing in Medina.

10. Why was the constitution of Medina important?

The Constitution of Medina was important because it established a framework for peaceful coexistence among diverse groups, promoted justice and equality, and laid the foundation for the first Islamic state.

Reference:

- “The First Written Constitution in the World: An Important Document of the Time of the Holy Prophet” by Dr. Muhammad Hamidullah

- Yaqeen Institute for Islamic Research:

- International Centre for Education in Islamic Civilisations: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/228245045_The_Medina_Constitution

- The Islamic Texts Project: https://ummatics.org/islamic-norms/the-constitution-of-medina-translation-commentary-and-meaning-today/